Table of Contents

Context: The article discusses two recent judgements delivered by the Supreme Court of India. The first case dealt with the issue of control over civil services in the government of Delhi and the second case pertains to the formation of the current government in Maharashtra, which occurred after a split within the Shiv Sena party. Overall, the article highlights the significance of these two judgements and their implications for the accountability of elected officials in the Indian political system.

Two Judgments and the Principle of Accountability Background

The article discusses the recent SC verdicts on the issue of control over civil services in Delhi and the political instability in Maharashtra.

- The judgement in the first case established that the elected Chief Minister of Delhi, and not the Lieutenant Governor appointed by the central government, has the authority to control the civil services working for the Delhi government.

- This judgement reinforces the principle of accountability by holding the Chief Minister accountable to the electorate.

- The verdict in the second case that pertains to the formation of the current government in Maharashtra, is seen to break the principle of accountability by implying that Members of Parliament (MPs) or Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs) are not accountable to the electorate.

- This is observed to undermine the concept of triple chain of accountability, which is an underlying principle established in the Delhi judgement regarding the control of civil servants.

Decoding the Editorial

The author expresses that there is a contradiction between the two judgments delivered by the Chief Justice of India. While both judgments provide a clear explanation of the constitutional position, the Maharashtra judgement contradicts a core principle established in the Delhi case.

- The contradiction arises from the fact that the Maharashtra judgement relies on the Tenth Schedule of the Indian Constitution, which pertains to the anti-defection law.

- The anti-defection law aims to prevent elected representatives from switching parties or betraying the party’s mandate on which they were elected.

- However, the author argues that this law is incompatible with the underlying structure of parliamentary democracy.

- Understanding the Delhi Case:

- The Delhi case involved the question of accountability of civil services in the Delhi government.

- The issue revolved around whether the civil services should be answerable to the Delhi cabinet or to the Union government.

- Delhi, being a Union Territory with a legislature, has powers and responsibilities outlined in Article 239AA of the Indian Constitution.

- In its judgement, the Supreme Court emphasised the principles of parliamentary democracy, which include a government being accountable to the people.

- The court explained that this accountability requires a triple chain of command: civil service officers being accountable to Ministers, Ministers being accountable to the legislature, and the legislature being accountable to the electorate.

- This clarifies that any disruption or severance of this triple chain of accountability would be contrary to the essence of parliamentary democracy.

- Therefore, the Supreme Court ruled that the civil services must report to the Delhi Cabinet, ensuring the accountability of the government to the people.

- Understanding Maharashtra Case:

- The Maharashtra judgement addressed a series of events involving different factions within the Shiv Sena party and their contradictory whips under the anti-defection law.

- The dispute arose when two factions of the party issued conflicting instructions, and the Maharashtra Speaker recognized the whip of one faction, which claimed to have more Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs), as the legitimate representation of the party.

- One of the key issues examined by the Supreme Court in this case was to determine which faction had the authority to appoint the leader and whip of the legislature party.

- This determination was crucial because it would grant the power to issue binding directions on every member of the party within the Assembly.

- The Court ruled that the Tenth Schedule makes a differentiation between the legislature party and the political party.

- The legislature party includes all MLAs/Members of Parliament belonging to the political party.

- It determined that the power to issue directions was with the political party, and not the legislature party.

- Therefore, the person in charge of the political party (who may not be a member of the legislature) would control every vote of the MLAs/MPs of that party.

- Failure to adhere to such direction by any MLA/MP would lead to disqualification.

- Thus, this judgement further entrenches the power of the party leadership over the legislature.

- It reinforces the idea that the MP/MLA is not accountable to the electorate but only to the party that fielded them in the election.

- In doing so, it breaks the triple chain of accountability, which is an underlying principle of the Delhi judgement.

Concerns Regarding the Maharashtra Judgement:

- The judgement in the Maharashtra case expresses concern about the possibility of legislators being elected based on their party affiliation but later disconnecting from that party.

- It emphasizes that the Tenth Schedule of the Indian Constitution is designed to prevent such situations.

- This stance differs from the position taken in the Delhi judgement.

-

- In the Delhi judgement, the Court highlights the importance of daily assessment of the government in the legislature through various means such as debates on bills, questions during Question Hour, resolutions, and no-confidence motions.

- The Court argues that if legislators of the party with a majority in the House are bound by the directions of the political party, the concept of daily assessment by the legislature becomes meaningless.

- This is because the party leadership would effectively control the votes of its legislators on every issue, ensuring that the government always emerges victorious in all votes, including no-confidence motions.

- The only way for a legislator to dissent would be to give up their membership in the House.

- The Maharashtra judgement takes a different stance from this regarding the relationship between legislators, party directions, and the functioning of the legislature.

- It sees the Tenth Schedule as a safeguard against legislators disconnecting from their affiliated parties, while the Delhi judgement emphasizes the importance of individual legislators having the ability to assess and hold the government accountable through their votes and participation in legislative proceedings.

Concern with the Anti-Defection Law:

- The concern with respect to the Anti-defection law, is that it assumes that any vote by an MP/MLA against the party’s directive is a betrayal of the electoral mandate.

- However, this interpretation of representative democracy is considered incorrect.

- It is argued that while party affiliation is an important factor for voters in elections, it is not the sole criterion.

- The Supreme Court has recognized this principle by mandating that candidates disclose information about their criminal record, assets and liabilities, and educational qualifications. This information is aimed at allowing voters to make informed decisions beyond just considering party affiliation.

-

- Examples: In Karnataka and Madhya Pradesh, where MLAs who defected from one party to another were re-elected when contesting on a different party ticket.

-

-

- This indicates that the electorate endorsed the individual candidate and not necessarily the original party they were affiliated with.

-

Therefore, the concern with the Anti-defection law is that it oversimplifies the complexity of voter preferences and undermines the ability of voters to make nuanced decisions based on various factors beyond party affiliation. It potentially restricts the independence and accountability of MPs/MLAs, as their actions are constrained by party directives rather than being responsive to the interests and will of their constituents.

Way Forward

- There is a need for a reevaluation and reexamination of the anti-defection law in order to uphold the principles of parliamentary democracy and accountability.

- This is because, it is argued that the current design of the anti-defection law disrupts the chain of accountability between the government and the legislature, as well as between legislators and their constituents.

- The anti-defection law requires legislators to adhere to party directives even if it compromises their ability to hold the government accountable.

- This undermines the daily accountability of the government to the legislature and weakens the legislators’ responsibility to justify their actions to their voters in every election.

- This violation of the central principle of parliamentary democracy is seen as contrary to the basic structure of the Constitution.

- A reexamination of the anti-defection law would require a larger Bench than the one that ruled on it in 1992.

- The Maharashtra judgement has already referred one aspect to a seven-judge Bench, specifically regarding the Speaker’s ability to decide on disqualification petitions while facing a notice of removal.

- The seven-judge Bench, while hearing this case, should expand the scope of the question to include an examination of whether the anti-defection law violates the basic structure of the Constitution.

- Ultimately, the aim should be to strengthen the democratic framework and restore the accountability of governments to the people they serve.

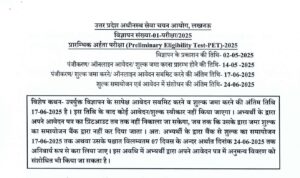

UPSSSC PET Notification 2025 Out: Apply ...

UPSSSC PET Notification 2025 Out: Apply ...

IMF’s Fiscal Monitor and Financial Sta...

IMF’s Fiscal Monitor and Financial Sta...

Cabinet Committee on Political Affairs (...

Cabinet Committee on Political Affairs (...