Table of Contents

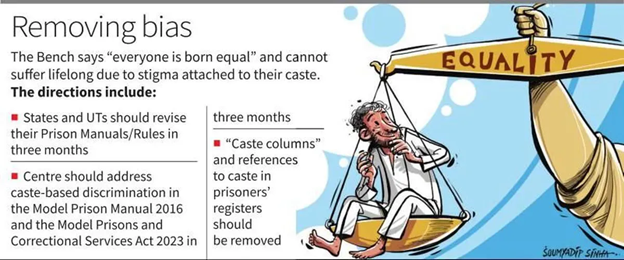

Context: The Supreme Court issued a set of directives to both the Centre and the states, mandating that no inmate should be assigned work or housing arrangements based on their caste.

More in News

- Under the present system, menial jobs of cleaning and sweeping are given to the marginalised communities, while the upper castes are assigned to work like cooking.

- Examples:

- In Rajasthan, the prison rules designated Mehtars (a lower caste) for latrine duties while assigning higher-caste prisoners to kitchen tasks.

- In Tamil Nadu, prisoners from communities like Thevars and Nadars were segregated into different sections of Palayamkottai Central Jail.

- Examples:

- The Supreme Court ruling highlighted that caste-based discrimination within prisons is a remnant of oppressive colonial and pre-colonial systems which were designed to dehumanise marginalised groups and these are deeply ingrained in institutional frameworks.

- The Court observed that prison regulations perpetuate historical stereotypes and social hierarchies.

- Such practices hinder personal growth and development for individuals from marginalised castes.

| Articles Violated By Such Practices |

|

Marginalised Communities in Jails: Data

- Prison Statistics India report 2021 revealed that the number of convicts in jails decreased by 9.5 per cent, whereas the number of undertrial inmates increased by 45.8 percent between 2016 and 2021.

- Over 3 out of 5 undertrial prisoners lodged across Indian prisons, are from Dalit, Adivasi and OBC communities, according to the latest Prison Statistics of India Report (2021).

- The latest National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data reveals that 94% of undertrials were from a Scheduled Caste, 9.26% belonged to a Scheduled Tribe, and 35.88% were from a socially and educationally backward community.

Reasons Behind High Number of Marginalised Communities in Prison

- Deeply Entrenched Prejudices: Societal biases against marginalised communities, such as Dalits and Adivasis, often manifest in the criminal justice system.

- These prejudices can influence police behaviour, judicial proceedings, and public perception, leading to discriminatory practices.

- Example: A study found that Dalits are disproportionately represented in custodial deaths and wrongful arrests due to systemic bias.

- Lack of Awareness: Many prisoners belonging to marginalised communities are unaware of their fundamental rights, the preamble, and their fundamental duties, contributing to their overrepresentation in jails.

- High Litigation Costs: Excessive costs involved in litigation act as a major barrier to accessing justice, leading to prolonged incarcerations.

- Cycle of Criminalisation: Once individuals from marginalised communities enter the criminal justice system, they may be repeatedly targeted and profiled for offences, perpetuating a cycle of criminalization and marginalisation.

- Criminalisation of Customary Practices: Customary practices of Adivasi communities are often criminalised without understanding their cultural context.

- Example: Tribal youths in Tamil Nadu’s Nilgiris district are routinely arrested under the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act for consensual relationships, a common practice among their community.

- Empathetic Handling Lacking: The prosecution system is often under-resourced and lacks adequate training, which leads to ineffective handling of cases (without sensitivity) involving marginalised communities.

Challenges faced by marginalised communities in Prison

- Custodial Abuse: Inmates from marginalized backgrounds often experience physical and sexual abuse within prisons. The lack of oversight and accountability allows such abuses to persist unchecked.

- Disconnection from Families: Family visits can be financially burdensome for marginalised inmates, leading to isolation and a breakdown of familial ties during incarceration.

- This disconnection further complicates their reintegration into society post-release.

- Inhumane Treatment: Conditions in prisons such as inadequate sanitation, food shortages, and rampant disease outbreaks disproportionately affect marginalised communities that already face systemic disadvantages

- Lack of Access: Many undertrial prisoners from marginalised backgrounds face significant barriers to obtaining legal aid.

- Although nearly 80% of the population qualifies for legal aid, only a small fraction has received assistance since the establishment of legal services institutions in 1987.

- Additionally, the quality of free legal services is often inadequate, leaving many individuals vulnerable to prolonged incarceration without proper representation.

Judicial Interventions

- The Supreme Court in Arnesh Kumar vs State of Bihar had stated that the police should ordinarily not arrest people if the offence they are charged with has a maximum sentence of less than or up to seven years.

- In all such offences, police should ordinarily not arrest, they should send a notice and only if the person doesn’t cooperate with investigation, only then they can arrest if they want.

- The Supreme Court Hussainara Khatoon v. Home Secretary, State of Bihar (1979) case ruled that keeping undertrial prisoners incarcerated for longer than their potential punishment constitutes a clear violation of their fundamental rights ( Article 21).

Way forward

- The idea of open prisons must be considered seriously.

- Need to strengthen Lok Adalats for minor offences such as traffic infringements, excise offences, shoplifting, and disorderly public conduct.

- There should be an alternative bail system. It should not be only financial.

- Better police training, more courts, more court halls, more court staff.

- Speedy trial can become an effective tool

- eg. Special fast-track courts to be set up to extensively deal with petty offences and for cases pending for five years or more

- Regularly monitor the progress of cases pending in courts.

- Application of AI in criminal case management.

GPS Spoofing and Its Impact in India: A ...

GPS Spoofing and Its Impact in India: A ...

Amrit Gyaan Kosh Portal: A Comprehensive...

Amrit Gyaan Kosh Portal: A Comprehensive...

UpLink Initiative: Launched by World Eco...

UpLink Initiative: Launched by World Eco...