Table of Contents

Context: The article is discussing India’s approach to conflict resolution and its multi-alignment stand, which refers to India’s strategy of maintaining friendly relations with multiple countries, including those that may have opposing interests or ideologies (policy to dehyphenation). The article argues that while India’s multi-alignment stand has given it some diplomatic space, it may not be sufficient for India to play the role of a mediator between Russia and Ukraine. It also highlights China’s recent mediation efforts to resolve the Ukraine crisis and how it has positioned itself in opposition to the American approach by exploiting differences among Western countries and further cementing the Beijing-Moscow relationship. India may not view its role in resolving the conflict in the same way and India has been increasingly using symbolic instruments of power to enhance its soft power appeal, such as projecting itself as a “moral force” to enforce global peace.

The Problem with India’s Multi-Alignment Stand Background

India’s foreign policy has evolved through various phases since its independence in 1947.

- Phase of Non-Alignment (1947-1962):

-

- The first phase was characterized by an optimistic non-alignment approach, which aimed to resist dilution of India’s sovereignty, rebuild its economy, and consolidate its integrity.

- India played a key role in establishing the Non-Alignment Movement (NAM) during this phase.

- Phase of Realism & Recovery (1962-71):

-

- The second phase saw a shift towards realism and recovery.

- India made pragmatic choices on security and political challenges and concluded a defense agreement with the US in 1964.

- However, India faced external pressures on Kashmir from the US and UK and began to tilt towards the USSR.

- Phase of greater Regional Assertion (1971-91):

-

- The third phase was marked by greater regional assertion as India showed remarkable use of hard power when it liberated Bangladesh in the India-Pakistan war in 1971.

- However, it was a particularly complex phase as the US-China-Pakistan axis that came into being at this time seriously threatened India’s prospects as a regional power.

- India faced sanctions from the US and its allies after conducting a peaceful nuclear explosion test in 1974.

- Phase of Safeguarding Strategic Autonomy (1991-98):

-

- The fourth phase was focused on safeguarding strategic autonomy, particularly with regards to securing India’s nuclear weapon option.

- India reached out to engage the US, Israel, and ASEAN countries more intensively.

- Phase of being a Balancing Power (1998-2013):

-

- The fifth phase saw India acquiring the attributes of a balancing power against the rise of China.

- India made common cause with China on climate change and trade while consolidating further ties with Russia and helping to fashion BRICS into a major global forum.

- Phase of Energetic Engagement (2013 to the present):

-

- In this phase, India’s policy of non-alignment turned into multi-alignment.

- India is now more aware of its own capabilities and the expectations that the world has of India.

- India has been able to assert itself beyond South Asia, through its approach towards the Indian Ocean Region and the extended neighborhood. India’s willingness to shape key global negotiations, such as the conference in Paris on climate change, is equally significant.

Decoding the Editorial

The article talks about India’s role in resolving the conflict via its soft power appeal, projecting itself as a “moral force” to enforce global peace.

- India’s view on Ukraine-Russia Conflict:

- India has been actively engaging with Ukraine and expressing solidarity with the Nation in the face of the ongoing conflict with Russia.

- This is in contrast to China’s move with Moscow in order to cement China’s relationship with Russia.

- India has been committed to supporting peace efforts in Ukraine and sees itself as a mediator in the conflict.

- The United States sees this engagement as important because it aligns with its own response to the conflict and helps to bring the two countries’ positions into closer alignment.

- India’s position as Vishwaguru/Global Teacher:

- India’s regular interactions with Ukraine are indicative of India’s rising stature and unique position in the emerging global order.

- Despite criticism from the West over India’s continued energy imports from Russia and export of refined Russian fuel to the European market, India is seen as seeking to establish itself as a global teacher and arbiter.

- Ukraine feels that supporting its cause is the only right choice for a true Vishwaguru, or global teacher.

- Thus, India’s pursuit of a Vishwaguru may be incomplete if it fails to take a strong moral position on Russia’s violation of Ukraine’s sovereignty.

- India’s Soft Power/Cultural Ethos:

- Nationalist ideas have long influenced the Indian state and society, and this has continued till the current foreign policy discourse.

- Indian governments have always emphasised on its cultural ethos and civilizational values as a source of its distinctiveness and influence in the world.

- Soft power, which is often associated with cultural and civilizational values, is an important component of India’s foreign policy strategy.

- However, soft power is also considered ambiguous and its impact on policy is often seen as limited.

- Soft power should be seen as a form of “nonmaterial” power that interacts with material resources or hard power, either enhancing their impact or compensating for their absence.

- India’s Hard Power Potential:

- India lacks hard power.

- This could be understood from the fact that had India had adequate material power, it could have stopped the Ukraine war.

- This assertion implies that a powerful Indian state would work towards global peace and stability.

- Lack of Clarity:

- India’s lack of clear stance on the Ukraine war, despite expressing disapproval, is contradictory to its aspirations of becoming a permanent member of the UNSC, which would require a commitment to speaking as a global voice against territorial aggression and rights violations.

- India’s ambiguity may be understandable given its traditional allies, but it does not align with the normative pillars of the Vishwa Guru identity, which emphasizes democratic, self-confident, and morally superior values.

- This implies that India cannot claim to be a moral global leader if it continues to maintain an evasive position on conflicts like the Ukraine war and that it should take a clearer stand on such issues to uphold its aspirations and ideals.

- Reasons for India’s ambiguity:

- India’s position on the Ukraine war is nuanced and reflects a balancing act between its traditional ties with Russia and its democratic values.

- While India has expressed disapproval of Russia’s military actions in Ukraine, it has avoided taking a clear position on the issue in many UN resolutions, which may be due to India’s military and geopolitical dependence on Russia.

- However, India’s views on sovereignty align with universally acceptable Westphalian notions and clash with China’s political philosophy of ‘might is right,‘ which has led to China’s support for Russia in the conflict.

- India’s pursuit of “multi-alignment”:

- India’s policy of “multi-alignment,” which refers to maintaining diplomatic relations with multiple countries while avoiding alignment with any particular bloc or alliance, has allowed it some diplomatic flexibility in the context of the Ukraine conflict.

- However, India’s lack of material resources means that it may not be able to effectively play the role of a mediator between Russia and Ukraine, and that China’s economic and military power far surpasses India’s.

- This limits India’s current diplomatic and strategic position in the context of the Ukraine conflict.

Beyond the Editorial

Strategies to be Adopted by India as a Leader of the Global South:

- Embrace Realism: India needs to adopt a more realistic approach towards foreign policy. Diplomatic visibility should not come at the cost of ignoring hard security realities. Adequate consultation with the military is necessary to avoid misreading the intentions of neighbouring countries.

- Build a Strong Economy: Economic power is crucial for expanding foreign policy options. India needs to focus on building a strong economic foundation to fulfill its aspirations of becoming a global power.

- Multi-Alignment is Necessary: Engaging multiple players is essential in today’s world, characterized by complex interdependence. Strategic hedging is necessary, but it can be a delicate exercise. India needs to reconcile the different groups it engages with, carefully weighing the potential risks and rewards.

- Take Greater Risks: India needs to be more assertive in participating in events of geopolitical significance, without fearing the potential risks. India’s humanitarian assistance and disaster relief operations are a statement of its capability and responsibility, but it needs to have a more prominent role in shaping global conversations.

- Proper understanding of World order: Proper understanding of world politics is necessary to avoid costly misreadings of larger landscapes. India needs to appreciate the relevance of Pakistan in the global strategies of the US and China, and the significance of Sino-US contradictions, multi-polarity, weaker multilateralism, and regional powers.

Therefore, India needs to work with multiple partners on different agendas while defining its interests more clearly. Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas, Sabka Vishwas is relevant to India’s foreign policy in this phase of geopolitical transformation.

World Population Day 2025, Themes, Histo...

World Population Day 2025, Themes, Histo...

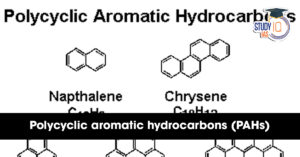

What are Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon...

What are Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon...

Marlin Fish: Species, Features, Appearan...

Marlin Fish: Species, Features, Appearan...