Table of Contents

Shah Bano Case

Both men and women have equal status and rights under Islamic personal law, according to the holy Quran. The reason why is questionable, though. Important subjects of discussion and vigorous debate have included education, polygamy, upkeep, and wearing of the headscarf. Mohd. Ahmad Khan v. Shah Bano Begum & Ors. (1985), popularly known as the Shah Bano case, is regarded as one of the turning points in the struggle for equality of Muslim women in India. It made it possible for thousands of women to assert rights that had previously been forbidden.

Shah Bano Case is an important part of Indian Polity which is an important subject in the UPSC Syllabus. Students can also go for UPSC Mock Test to get more accuracy in their preparations.

Shah Bano case Facts Associated

Mohd Ahmed Khan (appellant), a lawyer by trade, wed Shah Bano Begum (respondent) in 1932, and the two of them had three boys and two daughters. Shah Bano Begum, then 62 years old, was cast out of her husband’s home along with her kids in 1975. She filed an appeal with the Judicial Magistrate of First Class in Indore in 1978, requesting maintenance of Rs. 500 per month in accordance with Section 125 of the CrPC.

Then, since they were no longer husband and wife and had been paying maintenance of Rs. 200 per month for almost two years, her husband granted her an irrevocable triple talaq and cited that as a justification for not paying support. Additionally, he had paid the court a total of Rs. 3000 through dower during the iddat term.

The Magistrate ordered the spouse to pay Rs. 25 in maintenance in 1979. Shah Bano submitted a revisional plea to the MP High Court in 1980 to amend the maintenance payment, and the High Court increased it to Rs. 179 per month as a result. The husband then filed a special leave petition before the Supreme Court to contest this application.

Shah Bano case Issues Associated

- Does a divorced Muslim lady fit the description of wife under Section 125 of the Criminal Procedure Code?

- Whether the personal law is superseded by Section 125 CrPC?

- Why If section 125 of the CrPC and Muslim personal law clash, is a Muslim husband required to pay maintenance to a divorced wife under section 125 of the CrPC?

- What is the amount payable upon divorce under Section 127(3)(b) CrPC, and is Mehar or dower included in the amount payable upon divorce?

Overall, the main issue was that the husband’s case was entirely based on the claim that maintenance under Section 125 CrPC must be disregarded on the grounds that Muslim law absolves the husband of all obligations to his divorced wife, aside from paying any mahr due to her (dower paid in lieu of marriage by the husband) and an amount to cover maintenance during the iddat period, and Section 127(3)(b) CrPC conferring statutory recognition on this principle.

Also Read: Hindu Marriage Act

Shah Bano case & Iddat Meaning

Iddat is the waiting period a lady follows before getting married to another guy after her husband passes away or gets divorced. The length of the iddat term is contingent (often 3 months). The primary goal of iddat is to give the wife enough time to mourn her husband’s passing while also shielding her from criticism for getting remarried too soon after he passed away. Iddat also aids in confirming a woman’s pregnancy because, if there is one, a normal pregnancy lasts half that long, or four and a half months. As a result, let’s examine the time frame during which the iddat period was observed:

- A woman who has recently been divorced observes iddat for three months, whereas a woman whose husband has passed away observes iddat for four lunar months and ten days following his passing, regardless of intermarriage sexual activity.

- The woman’s period lasts till delivery after she becomes pregnant.

- If a woman is expecting a child at the time her husband passes away, she must observe iddat for an entire year, which includes the nine months of pregnancy as well as the three months of the iddat period.

The All India Muslim Personal Law Board backed the appellant’s (Mohd Khan) argument in Shah Bano’s case, arguing that courts cannot intervene in matters that are decided under Muslim personal law because doing so would violate “The Muslim Personal Law (Shariat Application Act, 1937)” and that any rulings on such issues must be made exclusively in accordance with Shariat.

Shah Bano Case Critical Analysis

In the Shah Bano Begum Case, the Supreme Court made it clear that Triple Talaq cannot be used to deny a divorced Muslim woman the right to support herself and her children if she is unable to do so at the time of her husband’s disapproval or divorce. When the Supreme Court rendered its decision in the Shah Bano Case, it received a great deal of criticism. At that time, Muslim women, whether they were married or not, were denied freedom, even their most basic freedom, which is against humanity and essentially violates the fundamental rights of people.

Compared to other women around the world, Muslim women have a lower status. In comparison to other women, they lacked education and independence. They encountered significant obstacles and issues, which caused their knowledge of numerous sects and level of confidence to decline. Along with these restrictions, individuals were also forbidden from working and from furthering their education. Since they had to deal with all of these issues since they were little children, it was only inevitable that they would struggle to make ends meet and maintain themselves. As a result, alimony or maintenance was crucial for them.

The Shah Bano case was a typical case like other maintenance cases that had occurred, and the Supreme Court’s ruling was also similar to earlier lawsuits, but the two naked truths that were seen in this case made it a landmark judgement case. The first naked truth was that the spirituality of religious personal laws was criticized, and the second naked truth was that it was questioned whether the Uniform Civil Code is applied to all religions and their practices.

Shah Bano Case Judgment

The Supreme Court issued a ruling in 1985 on the question of whether the CrPC, which is applicable to all Indian citizens regardless of faith, may be used in this situation. Additionally, personal laws would lose out to the CrPC.

Shah Bano received maintenance orders from the High Court according to the CrPC, which were affirmed by CJI Y.V. Chandrachud. Just that the maintenance amount was increased by the Supreme Court. According to him, Section 125 was created to quickly address the needs of a group of people who are unable to support themselves. What difference would it therefore make if the neglected wife, child, or parent practised a different religion?

The objective criteria that decide whether section 125 applies are the lack of care by a person of sufficient means to maintain them and their inability to sustain one. Such provisions, which are crucially preventative in nature, transcend religious boundaries. The obligation to support impoverished near relatives required by S. 125 is based on the individual’s responsibility to society to prevent vagrancy and misery. Religion and morality cannot be combined under the legal mandate of morality.”

Shah Bano Case UPSC

This case involved a Triple Talaq verdict, which in my opinion was a historic decision since it upholds the public’s trust in the legal system because, in this instance, “Justice and equality has overcome religion.” This lawsuit, in my opinion, was a turning point in the legal system because of the impartial, brave, and courageous conclusion that was made. This ruling has highlighted the significance of providing maintenance to divorced Muslim women who are unable to work and support themselves.

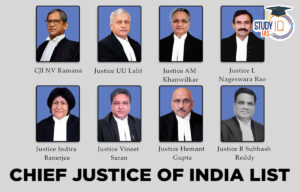

Justice BR Gavai will take oath as 52nd ...

Justice BR Gavai will take oath as 52nd ...

Right To Information Act, Objective, Fea...

Right To Information Act, Objective, Fea...

Indian Councils Act 1861, History, Provi...

Indian Councils Act 1861, History, Provi...