Table of Contents

The Supreme Court of India’s ruling on October 17, 2024, upheld the constitutional validity of Section 6A of the Citizenship Act, 1955, by a 4:1 majority. The judgment has raised significant concerns regarding constitutional violations and potential negative implications for Assam’s cultural and demographic landscape.

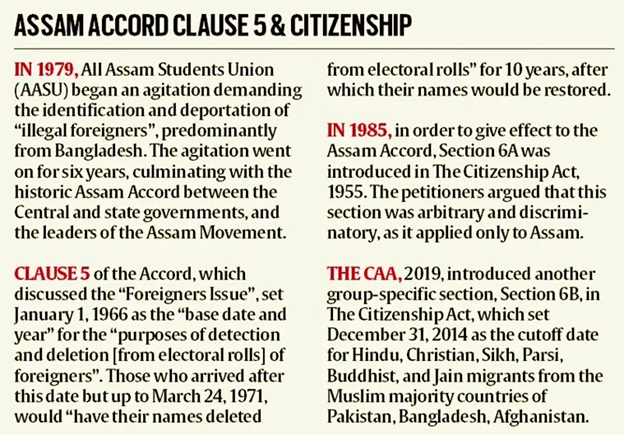

Section 6A of the Citizenship Act

- Section 6A was inserted into the Citizenship Act, 1955 via an amendment in 1985 following the signing of the Assam Accord.

- The provision establishes a special framework for granting Indian citizenship to migrants from Bangladesh (formerly East Pakistan) who settled in Assam before a specified date.

- Before January 1, 1966: Migrants who entered Assam before this date were automatically deemed Indian citizens.

- Between January 1, 1966, and March 25, 1971: Migrants who entered Assam during this period were required to register and would be granted citizenship after a 10-year residency period.

- After March 25, 1971: Migrants entering after this date were considered illegal immigrants and were subject to detection and deportation.

- This was designed to address the influx of migrants and the resultant socio-cultural and political tensions in Assam.

Flaws and Gaps in Supreme Court Ruling

- Inconsistent Reasoning Regarding Article 14 (Right to Equality)

- Court’s Justification:The Court justified the singling out of Assam for a distinct citizenship framework based on rational considerations, arguing that the impact of migration on Assam was more severe than on other states like West Bengal, Tripura, and Meghalaya.

- Flaw: The Court contradicted itself by acknowledging the disproportionate impact on Assam under Article 14 but later dismissing the cultural concerns under Article 29.

- This inconsistency indicates an arbitrary application of the equality principle.

- Contradictory Interpretation of Article 29 (Cultural Rights)

- Court’s View: The Court held that Section 6A does not infringe on Article 29 (right to conserve cultural identity), reasoning that migrants’ presence does not automatically hinder Assamese people from protecting their culture.

- Flaw: The Court overlooked the demographic and linguistic displacement caused by migration.

- The decline in the Assamese-speaking population (from 3% in 1951 to 48.38% in 2011) and the rise in the Bengali-speaking population (from 21.2% in 1951 to 28.91% in 2011) highlight the erosion of Assamese cultural identity.

- The Court’s abstract recognition of the right to “conserve” culture failed to address the real-world challenges of cultural preservation.

- Overlooking Temporal Unreasonableness

- Laws that were reasonable when enacted can become unreasonable over time.

- Section 6A, enacted in 1985, still allows for indefinite application of citizenship rules decades after the cut-off date (March 25, 1971).

- Flaw:

- The Court failed to acknowledge that the lack of a temporal limitation makes the law outdated and ineffective.

- 40 years after the Assam Accord, the provision no longer addresses the current migration challenges.

- Flawed Mechanism for Identifying Migrants

- State Burden: The process under Section 6A(3) places the burden of identifying illegal migrants on the state rather than on the individuals themselves.

- Flaw: The absence of a mechanism for voluntary self-identification results in delays and inefficiencies.

- The Foreigners’ Tribunals are overwhelmed, causing confusion and delaying the resolution of cases.

Background

Legal Points Addressed by the Court

Does Parliament Have the Power to Regulate Citizenship?

- Petitioners’ Argument: Section 6A allegedly altered the constitutional provisions related to citizenship (Articles 6 and 7) without a constitutional amendment.

- Court’s Response: The Supreme Court ruled that Articles 6 and 7 only pertained to determining citizenship at the time of the Constitution’s commencement in 1950.

- Section 6A, on the other hand, addresses later migrations from East Pakistan, and therefore does not conflict with these Articles.

- The court cited Article 11, which gives Parliament the authority to make laws regarding citizenship, affirming that Parliament has the right to create provisions for acquiring citizenship, such as those under Section 6A.

Does Section 6A Violate the Right to Equality?

- Petitioners’ Argument: They claimed that Section 6A violated the Right to Equality (Article 14) because it applies only to Assam and sets a different cut-off date for citizenship compared to other states.

- Court’s Response: The Court upheld the different treatment for Assam, citing the state’s unique situation due to the Assam Movement and the significant influx of migrants.

- It found the March 24, 1971, cut-off date to be reasonable, especially given the political and cultural context of Assam.

Does Section 6A Facilitate External Aggression?

- Petitioners’ Argument: They argued that allowing migrants to gain citizenship amounted to “external aggression,” as defined in the court’s earlier ruling in Sarbananda Sonowal vs Union of India (2005).

- Court’s Response: The court stated that Section 6A offers a controlled solution to migration, as opposed to the unregulated influx that would amount to external aggression.

- Also argued that interpreting Article 355 (which deals with the government’s responsibility to protect states from external aggression) in this way would lead to dangerous precedents, as it would give citizens the power to invoke emergency provisions inappropriately.

Does Section 6A Violate Indigenous Rights under Article 29?

- Petitioners’ Argument: They contended that granting citizenship to migrants from Bangladesh violated Article 29(1), which guarantees the protection of distinct cultural identities, claiming that the increase in the Bengali population eroded Assamese culture.

- Court’s Response: The Court disagreed, stating that the presence of diverse ethnic groups does not inherently infringe on the cultural rights of the Assamese people.

- Accepting this argument would threaten the concept of fraternity and social cohesion in a diverse nation like India.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court’s ruling on Section 6A raises critical constitutional concerns regarding cultural preservation and demographic integrity in Assam. The majority opinion’s reasoning appears insufficiently robust against established constitutional principles, particularly concerning Articles 14 and 29. As such, the ruling may have long-term negative implications for the Assamese identity and social fabric amid ongoing migration challenges

Places in News for UPSC 2025 for Prelims...

Places in News for UPSC 2025 for Prelims...

Right To Information Act, Objective, Fea...

Right To Information Act, Objective, Fea...

Indian Councils Act 1861, History, Provi...

Indian Councils Act 1861, History, Provi...