Table of Contents

Sati Pratha

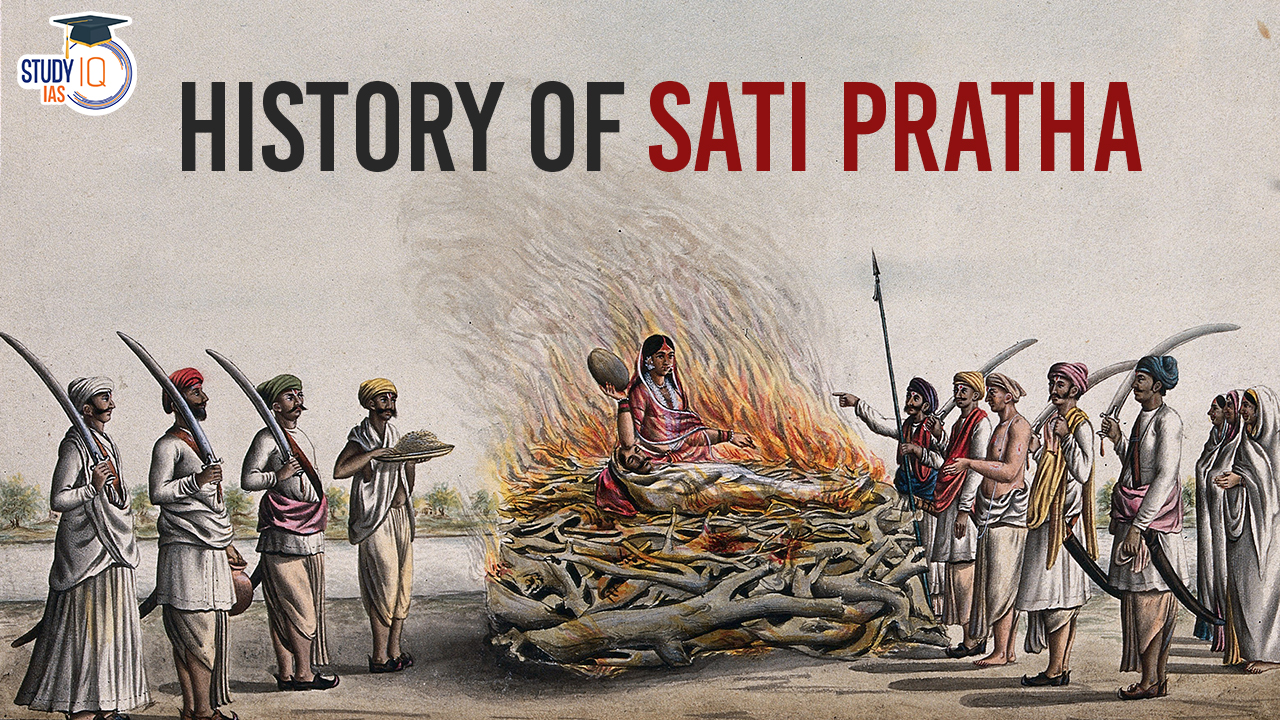

Sati Pratha, a practice steeped in the historical traditions of India, once prevailed in certain communities where widowed women would immolate themselves on their husband’s funeral pyre. This archaic ritual, though condemned by many, found justification among some Brahmin scholars and was perpetuated primarily among higher castes seeking to maintain social status.

Why did Practice of Sati Come into Existence?

The practice of Sati, while rooted in ancient Hindu beliefs and cultural norms, likely evolved for several reasons:

- Religious Devotion: Sati originated as a belief that immolating oneself on her husband’s pyre demonstrated the highest level of devotion and loyalty to him.

- Patriarchal Society: In ancient India, where patriarchal norms prevailed, Sati served to assert control over widows and enforce societal expectations.

- Property and Inheritance: Sati ensured that the husband’s property remained intact within the family, avoiding disputes over inheritance.

- Social Status and Prestige: Participation in Sati was often associated with elevated social status and honor, garnering respect and admiration.

- Fear of Widowhood: Some women may have chosen Sati to avoid the hardships and stigma associated with widowhood, seeking to maintain dignity and security.

Sati Pratha Overview

|

Sati Pratha Overview |

|

| Definition | Sati, derived from the Sanskrit word “asti,” meaning “She is pure or true,” is an ancient Hindu tradition where a widow immolates herself on her husband’s funeral pyre. |

| Origin | Initially voluntary, sati later became a coerced practice, symbolizing the duty of a wife to follow her husband into the afterlife. It was considered an act of devotion to the husband. |

| Historical Texts | The Mahabharata, compiled around 400 CE, contains explicit references to sati, with records suggesting its occurrence as early as the Gupta Period in 510 AD. |

| Regional Focus | Sati was notably prevalent in Rajasthan, particularly among women from royal families. |

| Legal Status | The Commission of Sati Prevention Act of 1987 officially outlawed sati in India, marking its prohibition by law. |

| Join Us on Whatsapp | Click to Join |

History of Sati Pratha in India

Sati Pratha, a custom embedded deep within the historical fabric of India, evokes both fascination and abhorrence in equal measure. This ancient tradition, wherein widowed women immolated themselves on their husband’s funeral pyres, carries a complex and multifaceted history shaped by cultural, religious, and social dynamics.

| Time Period | Description |

| Ancient Times | Sati, derived from the Sanskrit word “suttee,” was mentioned in ancient Indian scriptures and epics. It was rare and often depicted as an act of honor and devotion by widows. |

| Medieval Period | Sati became more prevalent during the medieval period, particularly under the influence of certain rulers and societal norms. |

| British Rule | The British East India Company initially attempted to regulate Sati, but it wasn’t until the early 19th century that they actively sought to abolish it due to ethical and humanitarian concerns. |

| Abolition | The Bengal Sati Regulation Act of 1829 was one of the earliest legislative measures aimed at abolishing Sati. It marked the beginning of formal efforts to eradicate the practice. |

| Legislative Efforts | Following the Bengal Sati Regulation Act, similar measures were passed in other parts of India, leading to the eventual abolition of Sati across the country. |

| Social Impact | The abolition of Sati was a significant step in challenging social norms and patriarchal structures in Indian society, although it was met with resistance and continued instances of the practice in isolated cases. |

Abolition of Sati Pratha

The abolition of Sati Pratha (the practice of widow immolation) occurred through a series of legislative and social reforms, marked by:

- Colonial Interventions: Colonial powers such as the British enacted laws to curb Sati. The Bengal Sati Regulation Act of 1829, under Lord William Bentinck, declared Sati illegal in British India, with severe penalties for those involved.

- Legal Challenges: The prohibition of Sati faced legal challenges, but landmark rulings, including the Privy Council’s affirmation of the ban in 1832, reinforced the abolitionist stance.

- Activist Movements: Reformers like Raja Rammohan Roy played a crucial role in advocating against Sati. Roy’s campaigns and writings raised awareness and garnered support for its abolition.

- Social Reform Movements: The broader social reform movements of the 19th century, including the Brahmo Samaj and Arya Samaj, actively opposed Sati and campaigned for its eradication.

- Public Opinion and Education: Increasing literacy and exposure to new ideas led to shifting societal attitudes, with condemnation of Sati becoming widespread among the educated populace.

- Enforcement and Penalties: Stringent enforcement of anti-Sati laws, along with severe penalties for offenders, deterred its practice and contributed to its decline.

- Continued Advocacy: Despite legal measures, advocacy groups and women’s organizations continue to raise awareness about the dangers and illegality of Sati, ensuring its eradication is upheld.

Contemporary Challenges and Perspectives

While legislation has provided a framework for combating Sati, challenges remain. Inconsistent enforcement and cultural attitudes pose significant hurdles. The National Council for Women (NCW) has proposed amendments to address shortcomings in the law, advocating for stricter penalties and more comprehensive measures to prevent Sati and protect vulnerable individuals.

Way Forward

The fight against Sati is not merely a legal battle but a cultural and societal transformation. Education, advocacy, and community engagement are crucial in eradicating deeply ingrained practices like Sati. By continuing to raise awareness, challenge outdated beliefs, and enforce stringent laws, India can ensure that Sati remains a relic of the past, consigned to history books rather than mournful funeral pyres.

In conclusion, the journey to abolish Sati reflects the ongoing struggle for human rights and gender equality in India. While legislative victories have been achieved, the battle against regressive practices demands constant vigilance and concerted efforts from all sections of society. The legacy of those who fought against Sati serves as a reminder of the power of collective action in bringing about meaningful change.

Jallianwala Bagh Massacre, Date, History...

Jallianwala Bagh Massacre, Date, History...

Buddhism History, Origin, Sect, Councils...

Buddhism History, Origin, Sect, Councils...

Rana Sanga: The Fearless Rajput King and...

Rana Sanga: The Fearless Rajput King and...