Table of Contents

Pressure Belts

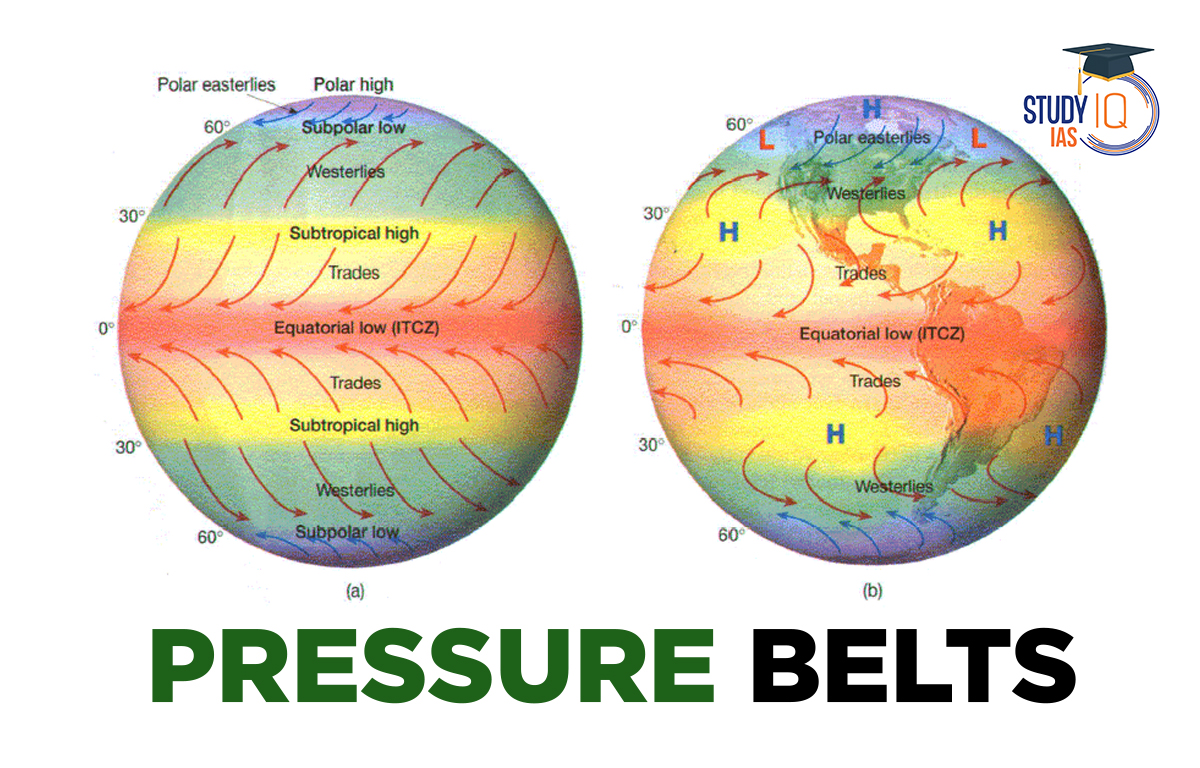

Pressure belts of the Earth are regions dominated by high or low atmospheric pressure. These belts alternate across the planet and are created by the uneven heating of the Earth’s surface by the sun. Warm air rises at the Equator, leading to low pressure, while cooler areas create high pressure.

Read More: Heat Zones of Earth

Pressure Belts Across the Latitudes

There are seven pressure belts:

- Equatorial low-pressure belt

- Sub-tropical high-pressure belt (Northern Hemisphere)

- Sub-tropical high-pressure belt (Southern Hemisphere)

- Sub-polar low-pressure belt (Northern Hemisphere)

- Sub-polar low-pressure belt (Southern Hemisphere)

- Polar high-pressure belt (Northern Hemisphere)

- Polar high-pressure belt (Southern Hemisphere)

Most of these belts have matching pairs in both hemispheres, except for the Equatorial low-pressure belt, which is unique to the equator. The Southern Hemisphere’s pressure belts are more continuous, while those in the Northern Hemisphere are more scattered. Atmospheric pressure varies from the equator to the poles due to temperature differences, Earth’s rotation, and water vapor. The pressure belts can be classified as either thermally induced or dynamically induced.

1. Equatorial Low-Pressure Belt

This belt extends from the equator to 10 degrees N and 10 degrees S latitudes. This belt is thermally produced due to heating by the Sun. As the sun shines almost vertically on the equator throughout the year, it heats the air and the warm air rises over the equatorial region and produces equatorial low pressure.

In this region, the air heats up so much that there is little horizontal movement, only vertical air currents. This area is known as the doldrums, or the “zone of calm,” because surface winds are almost nonexistent. It is also called the Inter Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) because the trade winds from the subtropical high-pressure belts come together here.

Read More: Seismic Waves

2. Sub-Tropical High-Pressure Belts

These high-pressure belts extend between 25 and 35 degrees latitude in both hemispheres. They form because rising air from the equator is pushed toward the poles and then cools and sinks, creating high pressure. The conditions here are calm with light, variable winds. In the Southern Hemisphere, small low-pressure areas can disrupt this belt in summer over Australia and South Africa. In the Northern Hemisphere, high pressure is mostly found over oceans, creating separate areas known as the Azores and Hawaiian cells.

These belts are also called Horse Latitudes because, in the past, ships carrying horses had trouble sailing here and often threw the horses overboard to lighten the load. Winds in these areas blow toward the equatorial and subpolar low-pressure zones, and upper-level winds converge, causing descending currents in the atmosphere.

Read More: Heat Transfer

3. Sub-Polar Low-Pressure Belt

The low-pressure belt extends along 60 degrees latitude in both hemispheres. Unlike the equatorial low-pressure belts, this one forms due to the Earth’s rotation. Winds from the subtropics and polar regions meet here and rise, creating cyclonic storms due to the temperature differences.

In the Southern Hemisphere, this low-pressure belt is stronger because of the large ocean area and is called the sub-Antarctic low. In the Northern Hemisphere, however, there are cold land masses at 60 degrees latitude, which increases the pressure and disrupts the continuity of the belt.

Read More: Weathering

4. Polar High-Pressure Belt

Cold temperatures cause air to compress, increasing its density, which leads to high pressure at the poles year-round. This high pressure is stronger over Antarctica than over the northern oceans. In the Northern Hemisphere, high pressure extends from Greenland to northern Canada rather than being centered at the pole.

The pressure belts we studied are not fixed, they shift north in July and south in January, following the Sun’s changing position between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn. Additionally, air pressure varies by location and season, influencing the weather and climate of different regions.

Read More: Solstices and Equinoxes

High and Low Pressure Belts

High-pressure areas known as subtropical highs can be found along 30° N and 30° S. Subpolar lows are low-pressure belts that extend further north and south along 60° N and 60° S. The polar high is characterised by high pressure near the poles.

Read More: Volcanic Eruptions

Shifting of Pressure Belts

The pressure belts as stated above would not exist if the earth were not inclined toward the sun. Because of the earth’s 23 1/2° inclination towards the sun, therefore, this is not the case. This tendency causes significant changes in the temperature of the continents, oceans, and pressure conditions in the month of January and July.

Pressure Belts January Condition

In January, the Sun moves south of the equator, causing the equatorial low-pressure belt to shift south. This leads to low pressure in South America, South Africa, and Australia, as the land heats up faster than the water. In the Southern Hemisphere, subtropical high-pressure areas form over the ocean. High-pressure belts are interrupted by land areas where temperatures are higher. Subtropical high-pressure cells are strong in the eastern oceans, where cold currents are present. In Asia, high pressure develops because land cools faster than the oceans.

Pressure Belts July Conditions

The equatorial low-pressure belt moves slightly north in July due to the Sun’s northward position. In Asia, low-pressure forms because land heats up faster than the ocean. The subtropical high-pressure areas are stronger over the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans in the Northern Hemisphere.

Read More: Interior of Earth

Pressure Belts UPSC

There are seven such pressure belts on the planet. Subtropical high-pressure belts can be found in both the northern and southern hemispheres at approximately 30 degrees latitude. This article will discuss an important phenomenon known as Pressure Belts in the context of the UPSC IAS Exam.

Story of Meera Bai and Her Devotion For ...

Story of Meera Bai and Her Devotion For ...

Desert Climate, Distribution, Climatic C...

Desert Climate, Distribution, Climatic C...

Deserts of India Map, Features of Thar D...

Deserts of India Map, Features of Thar D...