Table of Contents

Later Mural Traditions

Even after Ajanta, only few painting-containing sites have remained, offering important proof for reconstructing the painting history. Also worth mentioning is that the statues were painted and plastered. In numerous locations where carving and painting were done simultaneously, the tradition of cave excavations was carried on.

Badami

In Badami, Karnataka, there is a tradition of more recent murals. The western Chalukyan dynasty, which governed the area from 543 to 598 CE, had its capital there. In the Deccan, the Chalukyas consolidated their dominance after the Vakataka dynasty fell. Mangalesha, the Chalukya king, supported the excavations at the Badami caverns. He was Kirtivarman-I’s brother and the younger son of Chalukya king Pulikeshi I.

The patron (Mangalesha) mentions his Vaishnava allegiance in the inscriptions of cave No. 4, which is also known as the Vishnu cave. One of the paintings depicts Pulikeshi I’s son and Mangalesha’s older brother, Kirtivarman, witnessing a dance scene while seated within the palace with his wife and feudatories. In terms of style, the picture shows a continuation of the south Indian heritage of mural paintings from Ajanta to Badami.

The fluid forms, sinuously drawn lines, and compact composition demonstrate the artist’s ability and maturity in the sixth century CE. The beautifully rendered faces bring to mind Ajanta’s modelling aesthetic. Their lips are prominent, their eyes are half closed, and their eye sockets are huge.

Murals under Pallava, Pandava and Chola Kings

With regional variations under the rule of the Pallava, Pandya, and Chola kings, the painting tradition spread further south in Tamil Nadu in earlier centuries. In some regions of south India, the Pallava monarchs who succeeded the Chalukyas were also supporters of the arts. Temples were constructed in Panamalai, Mandagapattu, and Kanchipuram during the tenure of Mahendravarman (a Pallava).

The Mandagapattu inscriptions refer to Mahendravarman I by a number of names, including Vichitrachitta (curious), Chitrakarapuli (tiger among artists), and Chaityakari (temple builder), demonstrating his interest in artistic pursuits. Rajasimha, the Pallava ruler, was a patron of the paintings at the Kanchipuram temple. When compared to paintings from the preceding era, these paintings stood out for their increased decoration. When the Pandyas gained control, they too supported the arts. Some of the remaining examples include the Jaina caves in Sittanvasal and Tirumalaipuram.

The Chola monarchs, who governed the area from the ninth to the thirteenth centuries, continued the habit of constructing temples and adorning them with sculptures and paintings. The greatest examples of Chola art and architecture, however, didn’t arise until the 11th century, when the Cholas were at the height of their dominance. Rajaraja and Rajendra Chola constructed the Brihadeswara temples in Tanjore, Gangaikonda Cholapuram, and Darasuram.

At the Nartamalai and Brihadeswara temples, you can observe the significant Chola era paintings. The paintings of the Brihadeswara temple were done on the walls of the confined space that around the shrine. When they were found, there were two layers of paint. The upper/outer layer was painted in the 16th century, during the Nayaka era. Shiva in Kailash, Shiva as Tripuranartaka, Shiva as Nataraja, a portrait of Rajaraja and his teacher Kuruvar, dancing figures, etc. are all depicted in the Chola paintings at Brihadeswara.

Vijayanagara

The Vijayanagara dynasty, with Hampi as its capital, seized and established dominance over the region from Hampi to Trichy with the decline of the Chola dynasty in the 13th century. The paintings created in the 14th century in Tiruparakunram, close to Trichy, represent the beginning of the Vijayanagara style. The mandapa ceiling of the Virupaksha temple at Hampi, Karnataka, is painted with scenes from dynasty history and passages from the Ramayana and Mahabharata.

One of the significant panels is the one that depicts Vidyaranya, Bukkaraya Harsha’s spiritual guide. On the walls of the Shiva temple in Lepakshi, near Hindupur, in the current state of Andhra Pradesh, there are magnificent specimens of Vijayanagara artwork. As can be seen in the paintings from the Nayaka period, artists in different parts of south India adopted the stylistic norms of the next centuries.

Thiruparakuram, Sreerangam, and Tiruvarur (all in Tamil Nadu) are three locations where you can find Nayaka paintings from the 17th and 18th centuries. In Tiruparakunram, paintings from the 14th and 17th centuries are present. Vardhamana Mahavira is shown in earlier paintings in various moments of his life. The Nayaka paintings show scenes from Krishna Leela as well as images from the Mahabharata and Ramayana. There is a panel in Tiruvarur that tells the tale of Machukunda. The Ramayana is told in 26 panels in the Srikrishna temple at Ehengam in the Arcot District, which represents the final stage of the Nayaka paintings.

According to the examples, Nayaka paintings were essentially a continuation of Vijayanagara style with a few minor regional additions and alterations. Most of the time, the backgrounds are flat, and the masculine figures are depicted with thin waists but less pronounced abdomens than those from Vijayanagara.

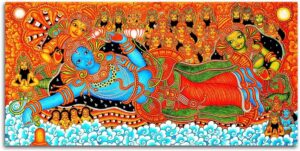

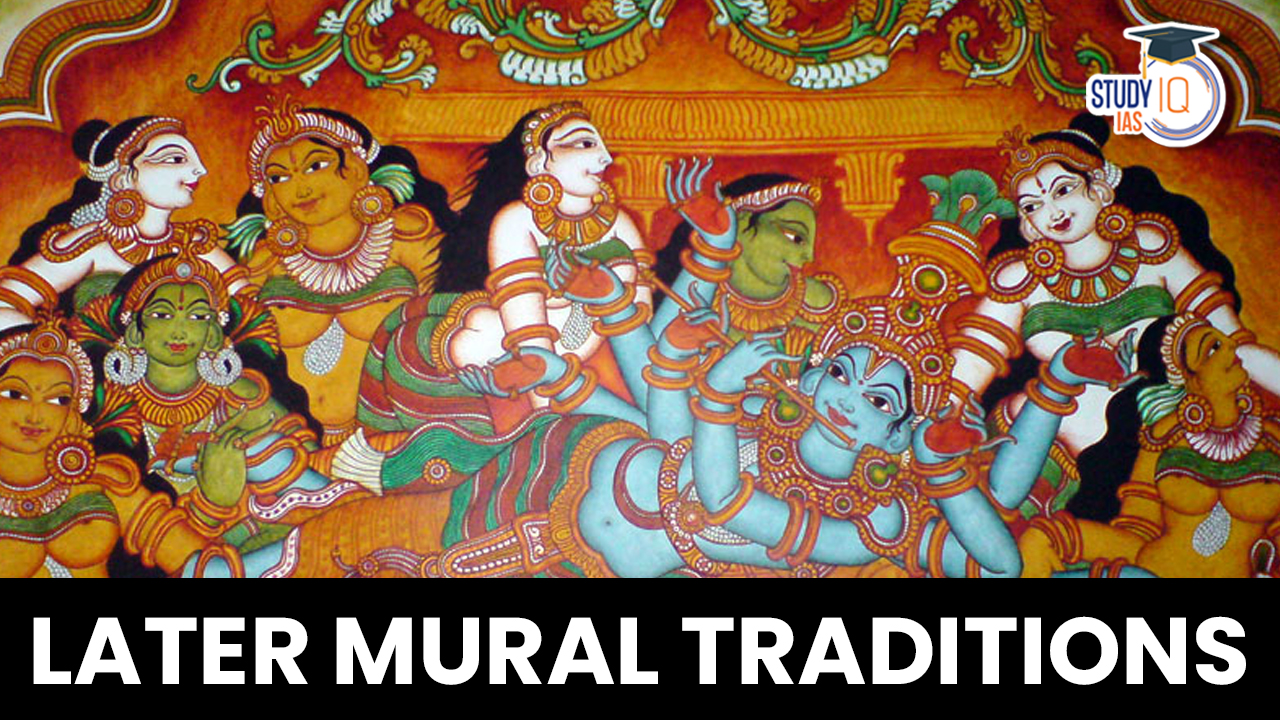

Kerala Mural

From the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries, Kerala artists developed their own pictorial language and technology while selectively incorporating certain aesthetic elements from the Nayaka and Vijayanagara schools. With the help of modern traditions like Kathakali and Kalam Ezhuthtu, the artists developed a language that used vivid and dazzling colours to depict human beings in three dimensions.

From the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries, Kerala artists developed their own pictorial language and technology while selectively incorporating certain aesthetic elements from the Nayaka and Vijayanagara schools. With the help of modern traditions like Kathakali and Kalam Ezhuthtu, the artists developed a language that used vivid and dazzling colours to depict human beings in three dimensions.

Murals have been discovered at more than 60 sites. The Dutch Palace in Kochi, Krishna Puram Palace in Kayamkulam, and Padmanabhapuram Palace are among the notable palaces where mural paintings can be discovered. Pundareekapuram Krishna Temple, Panayanarkavu, Thirukodithanam, Tripayar Sri Rama Temple, and Thrissur Vadakkunnatha Temple are examples of Kerala’s mature mural heritage.

Some of the other traditional Murals List

- Pithora – Rajasthan and Gujarat.

- Maithili – Bihar

- Warli – Maharashtra

Jallianwala Bagh Massacre, Date, History...

Jallianwala Bagh Massacre, Date, History...

NCERT Books for UPSC Preparation, Check ...

NCERT Books for UPSC Preparation, Check ...

UPSC Syllabus 2025, Check UPSC CSE Sylla...

UPSC Syllabus 2025, Check UPSC CSE Sylla...