Table of Contents

Isotherms

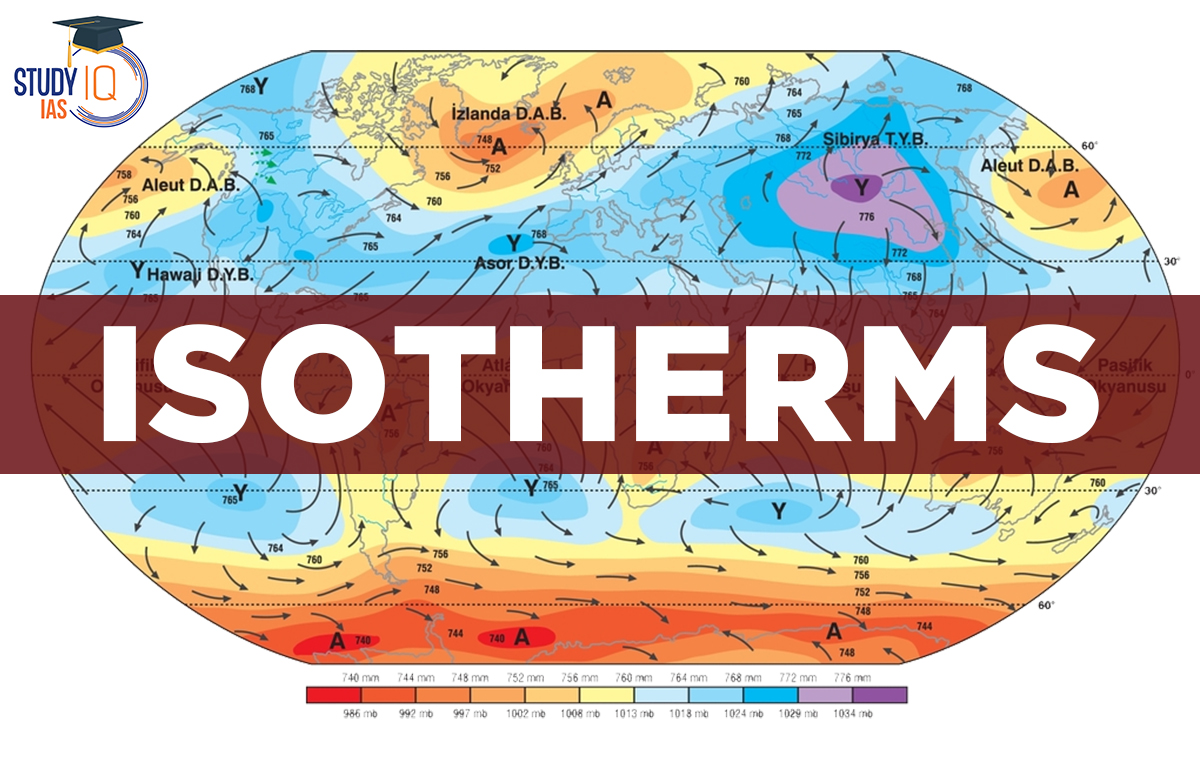

Isotherms are a line connecting points on a map that are the same temperature at a certain time or on average over a certain period of time. For example, on a world map, you might see two points with the same temperature one in South America and another in central Africa. To make an isothermal map, you would connect those two points with a line called an isotherm.

Features of Isotherms

- Isotherms and Temperature:

- Isotherms are lines on a map that show where temperatures are the same.

- They usually run parallel to the equator.

- Temperatures get cooler as you move toward the poles.

- The distance between isotherms indicates how fast temperatures change:

- Close together: Temperature changes quickly.

- Far apart: Temperature changes slowly.

- Isotherms in January:

- In January, isotherms move north over the sea and south over land.

- This happens because of temperature differences between land and water and warm ocean currents.

- For example, the Gulf Stream warms the Northern Atlantic Ocean, making isotherms bend north.

- In Europe, isotherms bend south as temperatures drop.

- Specific Temperature Example:

- In January, along the 60° E longitude, the average temperature is -20°C at both 80° N and 50° N latitudes.

- Southern Hemisphere:

- There is less land, so isotherms are more parallel to latitude lines.

- This shows a gradual temperature change compared to the northern hemisphere.

- In July, isotherms for:

- 20°C are at 35°S.

- 10°C are at 45°S.

- 0°C are at 60°S.

- These isotherms generally follow latitude lines.

Isotherms Temperature Distribution

The distribution of global temperatures can best be understood by studying the Isotherms. Isotherms are lines that cover areas of equal temperature. As mentioned earlier, latitudes have a big impact on temperature, and isotherms are usually linked to latitude. Changes from this trend are more noticeable in January than in July. In the northern hemisphere, there is much more land area than in the southern hemisphere, so the effects of land and ocean currents are more apparent.

Isotherms Lines

By examining the temperature distribution in January and July, it is possible to comprehend the global distribution of temperature. Isotherms are typically used to depict the temperature distribution on a map. The lines connecting locations with the same temperature are known as isotherms. Since the isotherms are typically parallel to the latitude, the effect of the latitude on temperature is frequently well-pronounced on the map. Particularly in the northern hemisphere, the departure from this overall pattern is more pronounced in January than in July.

The land surface area of the northern hemisphere is significantly larger than that of the southern hemisphere. As a result, the impacts of landmass and ocean currents are rather noticeable.

Seasonal Temperature Distribution – January

In January, the northern hemisphere experiences winter, while the southern hemisphere experiences summer. Because Westerlies can carry high temperatures into landmasses, the western margins of continents are warmer than their eastern counterparts.

The temperature gradient is close to the continents’ eastern margins. In the southern hemisphere, isotherms behave more consistently.

Northern Hemisphere

Isotherms shift north over the ocean and south over land, especially in the North Atlantic Ocean. Warm ocean currents like the Gulf Stream warm the Northern Atlantic, causing isotherms to move north, showing that these oceans can carry warm temperatures.

In contrast, a southward bend in isotherms over northern continents means the land is colder, allowing polar cold winds to move south, especially noticeable in the Siberian plain. Northern Siberia and Greenland have the coldest temperatures.

Southern Hemisphere

The ocean has a strong influence in the southern hemisphere. The isotherms are more or less parallel to the latitudes here, and the temperature variation is more gradual than in the northern hemisphere. The high-temperature belt runs along 30°S latitude in the southern hemisphere.

The thermal equator runs parallel to the geographical equator (because the Intertropical Convergence Zone or ITCZ has shifted southwards with the apparent southward movement of the sun).

Seasonal Temperature Distribution – July

In July, the northern hemisphere experiences summer, while the southern hemisphere experiences winter. The isothermal behaviour is inverse to that of January.

Isotherms in July generally run parallel to latitudes. The equatorial oceans experience temperatures of more than 27°C. More than 30°C is observed over land in Asia’s subtropical continental region, along the 30° N latitude.

North Hemisphere

In the northeastern part of the Eurasian continent, the temperature range is more than 60°C. This is due to the continent’s size. In contrast, the smallest temperature range, only 3°C, is found between 20°S and 15°N. The isotherms (lines of equal temperature) curve northward over northern continents, showing that these areas are overheated, allowing hot tropical winds to move far inland.

In the northern oceans, the isotherms shift southward, meaning the oceans are cooler and help moderate temperatures in tropical regions. Greenland has the coldest temperatures, while northern Africa, West Asia, northwest India, and the southeastern United States experience the highest temperatures. The temperature pattern in the northern hemisphere is irregular and zigzagging.

Southern Hemisphere

In the southern hemisphere, the temperature gradient becomes steady, with a slight curve towards the equator at the edges of the continents. The thermal equator is now positioned north of the geographical equator.

Vertical Distribution of Temperature

The normal lapse rate is the same at any height in the troposphere. At the Tropopause, the lapse rate stops changing, meaning the temperature stays the same there. In the lower stratosphere, the lapse rate remains constant for a while. However, temperatures are higher over the poles because this layer is closer to the Earth at those locations.

Adsorption Isotherm

An adsorption isotherm is a graph that shows how much of a substance (adsorbate) sticks to a surface (adsorbent) at a constant temperature and pressure. According to Le Chatelier’s principle, when pressure changes, the system reacts to balance itself. If the pressure gets too high, the system will adjust to lower the pressure by reducing the number of molecules inside.

The graph also shows that once the pressure reaches a certain point (called saturation pressure), the amount of substance sticking to the surface stops increasing. This is because there’s only so much space available for the substance to stick, and when all the spots are full, more pressure doesn’t change anything.

Adsorption Isotherm Types

Various scientists have proposed various types of Adsorption Isotherms, including:

- Langmuir Isotherm

- Freundlich Isotherm

- BET Theory

Since this topic (adsorption Isotherm) is related to organic Chemistry part so to avoid any kind of confusion we won’t be getting into the detail.

Role of Teachers in Educations, Student ...

Role of Teachers in Educations, Student ...

India's achievements after 75 years of I...

India's achievements after 75 years of I...

Bal Gangadhar Tilak Biography, Achieveme...

Bal Gangadhar Tilak Biography, Achieveme...