Table of Contents

Context: External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar has acknowledged challenges in providing dual citizenship but noted ongoing discussions about the issue. The government has considered expanding OCI benefits as a way to strengthen ties with the Indian diaspora without granting full dual citizenship.

Constitutional Provisions: Articles 5 to 11

- Article 5: Citizenship at the Commencement of the Constitution

- People residing in India on 26th January 1950 were granted citizenship if they:

- Were born in India, or

- Had either parent born in India, or

- Resided in India for at least five years immediately before the commencement of the Constitution.

- People residing in India on 26th January 1950 were granted citizenship if they:

- Article 6: Rights of Citizenship of Certain Persons Who Migrated to India from Pakistan

- Migrants from Pakistan before 19th July 1948 could acquire Indian citizenship if they:

- Had been residing in India since their migration, or

- Registered themselves as citizens after having lived in India for at least six months before registration.

- Migrants from Pakistan before 19th July 1948 could acquire Indian citizenship if they:

- Article 7: Rights of Citizenship of Certain Migrants to Pakistan

- Those who migrated to Pakistan after 1st March 1947 but later returned to India under a permit for resettlement could become citizens through registration.

- Article 8: Rights of Citizenship of Indians Living Abroad

- People of Indian origin residing outside India (in territories where their ancestors were born in India) could register as citizens with Indian diplomatic or consular offices.

- Article 9: No Dual Citizenship

- Anyone voluntarily acquiring citizenship of another country would lose their Indian citizenship.

- Article 10: Continuance of Rights

- Provisions of citizenship as provided by law shall continue unless altered by Parliament.

- Article 11: Power of Parliament

- Empower Parliament to make laws regarding the acquisition and termination of citizenship.

Citizenship Act of 1955

The Citizenship Act of 1955, enacted by Parliament under Article 11, outlines the methods for acquiring and terminating citizenship in India.

Modes of Acquiring Citizenship

- By Birth: Born in India on or after 26th January 1950 but before 1st July 1987 – automatically a citizen.

- Born between 1st July 1987 and 2nd December 2004 – a citizen if one parent is an Indian citizen.

- Born on or after 3rd December 2004 – a citizen if one parent is an Indian citizen and the other is not an illegal migrant.

- By Descent: Born outside India to an Indian citizen parent, subject to registration with an Indian consulate within one year.

- By Registration: Granted to persons of Indian origin or those married to Indian citizens after fulfilling residence requirements.

- By Naturalization: Granted to a foreigner who has resided in India for at least 12 years and meets other conditions.

- By Incorporation of Territory: If a foreign territory becomes part of India, the government specifies the people who shall be citizens.

Modes of Losing Citizenship

- By Renunciation: Voluntarily giving up Indian citizenship.

- By Termination: Automatically terminated if a citizen acquires foreign citizenship.

- By Deprivation: The government can revoke citizenship if obtained fraudulently or if the person acts against the country’s interests.

Types of Residents in India

- Citizen: Full political and civil rights under the Constitution, including voting, holding public office, and property rights.

- Acquired through birth, descent, registration, naturalization, or incorporation of territory.

- Non-Resident Indian (NRI): Indian citizens residing abroad temporarily for education, employment, or other purposes.

- Have Indian passports but limited rights (e.g., no voting rights while abroad).

- Persons of Indian Origin (PIO): Foreign citizens of Indian origin (up to four generations removed) who are not citizens of Pakistan, Bangladesh, or certain other countries.

- Previously held PIO cards (now merged with OCI).

- Overseas Citizen of India (OCI): A status granted to foreign nationals of Indian origin.

- Provides certain benefits like visa-free travel and property rights but excludes voting, holding public office, and certain government jobs.

- Foreigners: Non-citizens who are not of Indian origin and require visas to stay in India.

- Subject to the Foreigners Act, 1946.

- Illegal Migrants: People who enter India without valid travel documents or remain beyond their visa period.

- Governed by the Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019, in some cases, and are generally subject to deportation.

| Amendment |

Asian Countries That Allow Dual Citizenship

|

Arguments in Favor of Dual Citizenship

- Strengthening Diaspora Ties: Dual citizenship could deepen emotional and cultural ties with the Indian diaspora, encouraging them to contribute to India’s development and global influence.

- Economic Contributions: The diaspora could play a larger role in investments, technology transfer, and business collaborations, boosting India’s economy.

- Global Mobility and Flexibility: Granting dual citizenship may help Indian-origin individuals living abroad retain stronger links with their heritage without giving up opportunities in their adopted countries.

- Soft Power Enhancement: A robust diaspora with dual citizenship could act as informal ambassadors, strengthening India’s diplomatic and trade relations.

- Precedents in Other Countries: Several countries, like the U.S. and the U.K., allow dual citizenship without significant issues. Adopting this approach might align India with global practices.

Arguments Against Dual Citizenship

- Divided Loyalties: Dual citizenship could lead to conflicting political loyalties, particularly during international disputes involving India and other nations.

- Erosion of Sovereignty: Allowing dual citizens to vote and influence policymaking may give individuals with foreign loyalties a say in India’s internal matters, threatening national sovereignty.

- Administrative and Legal Complexities: Managing dual citizenship would introduce challenges in areas like taxation, legal disputes, and law enforcement, especially if conflicts arise between the two countries’ laws.

- Security Risks: Dual citizens could exploit their status for espionage, illegal financial activities, or other actions harmful to India’s interests.

- Unequal Treatment: The privileges of dual citizenship could disproportionately favour wealthier and well-placed diaspora communities, leading to socio-economic imbalances.

- Political Manipulation: There is a risk of foreign influence on India’s political processes, especially if dual citizens are allowed to vote or hold public office.

Countercyclical Capital Buffer (CCyB): P...

Countercyclical Capital Buffer (CCyB): P...

STELLAR Model: A Game-Changer in Power S...

STELLAR Model: A Game-Changer in Power S...

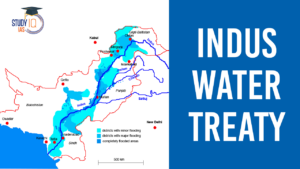

Indus Water Treaty 1960 Suspension Hurts...

Indus Water Treaty 1960 Suspension Hurts...