Table of Contents

Context: The article is discussing India’s paradoxical situation of being self-sufficient in food production but still facing food insecurity. It suggests that India needs a strategic initiative to eliminate food insecurity and ensure affordable access to food, especially for young children, to achieve the goal of zero hunger. This comes in the backdrop of a troubling statistic from the fifth National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5) data, conducted in 2019-21, that has brought to light the issue of hunger that is prevalent especially among young children.

India’s Hunger Paradox Background

What is Food Security?

- Food security refers to the state in which all individuals in a country have access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and preferences for an active and healthy life.

- This involves various dimensions such as:

- Availability of food through production and imports

- Accessibility of food without any discrimination, and

- Affordability of food for everyone.

- Therefore, food security is achieved only when there is adequate food available for all individuals, they have the means to purchase food of acceptable quality, and there are no barriers preventing access to food.

Food Insecurity:

- Food insecurity refers to the lack of consistent access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food necessary for an active and healthy life.

- It can be caused by factors such as poverty, conflict, natural disasters, climate change, and inadequate food distribution systems.

- Food insecurity can lead to malnutrition, stunted growth, chronic diseases, and other health problems.

Framework for Food Security in India:

In the 2022 Global Hunger Index, India ranked 107th out of the 121 countries. With a score of 29.1, India has a level of hunger that is serious.

- Right to Food: The Indian Constitution does not explicitly mention the right to food, but the fundamental right to life (Article 21) can be interpreted to include the right to live with human dignity, which may include access to food and other basic necessities.

- Buffer Stock: The Food Corporation of India (FCI) is responsible for procuring food grains at minimum support price (MSP) and storing them in warehouses across the country. These food grains are then supplied to state governments as and when required.

- Public Distribution System (PDS): The PDS is an important part of the government’s policy for managing the food economy in India.

- The PDS is meant to be supplemental and is not intended to provide the entire requirement of any commodity.

- Currently, the PDS distributes wheat, rice, sugar, and kerosene to the states and union territories.

- Some states and UTs also distribute additional items like pulses, edible oils, iodized salt, and spices through PDS outlets.

- National Food Security Act (NFSA), 2013:

- Launch: The Union government has notified the National Food Security Act (NFSA), in 2013.

- Objective: To provide for food and nutritional security in the human life cycle approach, by ensuring access to adequate quantity of quality food at affordable prices to people to live a life with dignity.

- Implementing agency: The Act provides for State Food Commission (SFC) in every State/UT, for the purpose of monitoring and review of implementation of the Act.

- Salient features of the Act:

| Coverage |

|

| Beneficiaries and Entitlement | There are two categories of beneficiary households under the NFSA:

|

| Nutritional Support to women and children | Pregnant women and lactating mothers and children (6-14 years) will be entitled to meals as per prescribed nutritional norms under Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) and Mid-Day Meal (MDM) schemes.

Higher nutritional norms have been prescribed for malnourished children up to 6 years of age. |

| Maternity Benefit | Pregnant women and lactating mothers will also be entitled to receive maternity benefits of not less than Rs. 6,000. |

| Women Empowerment | Eldest woman of the household of age 18 years or above to be the head of the household for the purpose of issuing ration cards. |

| Assistance by central government | The Central Government will provide assistance to States in meeting the expenditure incurred by them on transportation of foodgrains within the State, its handling and FPS dealers’ margin as per norms to be devised for this purpose. |

| Food Security Allowance | Provision for food security allowance to entitled beneficiaries in case of non-supply of entitled foodgrains or meals. |

- Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana:

- Launch: It is a food security welfare scheme announced by the Government of India in March 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic in India.

- It was announced as a part of the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana, which is a comprehensive relief package of Rs 1.70 Lakh Crore for the poor to help them fight the battle against Coronavirus.

- Implementing agency: The program is operated by the Department of Food and Public Distribution under the Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution.

- Objective: It is aimed at providing free foodgrains — 5 kg per person per month — to eligible beneficiaries of the National Food Security Act (NFSA), 2013. This is over and above their monthly entitlement under the NFSA.

- How is the PM-GKAY different from the NFSA?

- The NFSA is a right-based scheme under a law of Parliament, while the PM-GKAY is a scheme announced by the executive as a top-up to the entitlements under the NFSA.

- The PM-GKAY provides additional benefits to NFSA beneficiaries, but does not cover additional beneficiaries beyond the accepted limit of 81.35 crore persons under the NFSA.

Other Initiatives

India has taken several initiatives to achieve food security and end hunger, including:

- Mid-day Meal Scheme: The Mid-day Meal Scheme provides hot, cooked meals to school children to improve their nutritional status and increase school attendance.

- Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) Scheme: The ICDS Scheme provides a package of services, including supplementary nutrition, health check-ups, and pre-school education, to young children and pregnant and lactating mothers.

- Mission Poshan 2.0: Launched in 2021, Mission Poshan 2.0 is a flagship programme dedicated to maternal and child nutrition, with a focus on food-based initiatives to achieve the SDG of zero hunger.

- National Nutrition Mission (Poshan Abhiyaan): Launched in 2018, the mission aims to reduce malnutrition among children, adolescent girls, and pregnant and lactating mothers by providing nutritional supplements and promoting behavioural change through community mobilization.

- Agriculture and Rural Development Initiatives: India has various agriculture and rural development initiatives to increase food production, enhance rural livelihoods, and reduce poverty, such as the Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana, Pradhan Mantri Krishi Sinchai Yojana, and Deen Dayal Antyodaya Yojana-National Rural Livelihoods Mission.

Challenges to Food Security in India: India, one of the world’s largest producers of food, faces several challenges related to food security that include:

- Depleting Soil Health: Healthy soil is crucial for food production, but nearly one-third of the world’s soil is already degraded. Soil degradation in India due to excessive or inappropriate use of agrochemicals, deforestation, and natural calamities is a significant challenge to sustainable food production.

- Invasive Weed Threats: In the past 15 years, India has faced more than 10 major invasive pest and weed attacks. The Fall Armyworm destroyed almost the entire maize crop in the country in 2018, and locust attacks were reported in districts of Rajasthan and Gujarat in 2020.

- Inefficient Management Framework: India lacks a strict management framework for food security. The Public Distribution System faces challenges like leakages and diversion of food-grains, inclusion/exclusion errors, fake and bogus ration cards, and weak grievance redressal and social audit mechanisms.

- Gaps in Procurement: Farmers have diverted land from producing coarse grains to the production of rice and wheat due to a minimum support price. Furthermore, there is tremendous wastage of around Rs.50,000 crore annually due to improper accounting and inadequate storage facilities.

- Climate Change: Changing precipitation patterns and growing frequency and intensity of extreme weather events such as heatwaves, floods are already reducing agricultural productivity in India, posing a serious threat to food security. The monsoon accounts for around 70% of India’s annual rainfall and irrigates 60% of its net sown area.

- Supply Chain Disruption Due to Unstable Global Order: At a time when the Covid-19 Pandemic had already impacted food supply around the world in 2020, the Russia-Ukraine War in 2022 has disrupted the global supply chain and resulted in food scarcity and food inflation.

- Russia and Ukraine represent 27% of the world market for wheat, and 26 countries, mainly in Africa, West Asia and Asia, depend on them for more than 50% of their wheat imports.

Decoding the Editorial

The article is discussing a concerning statistic from the fifth National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5) conducted in India between 2019 and 2021.

Key Observations of the Survey:

- Issue of “Zero Food”: Among mothers with children aged between 6-23 months, a significant percentage of children did not consume any food in the 24 hours preceding the survey.

- This is referred to as “zero-food” and is a cause for concern as it indicates a lack of access to adequate food and nutrition for young children.

- The prevalence of zero-food is particularly high among infants aged 6-11 months, with 30% of them not consuming any food, and while the percentage decreases for older children, it remains worryingly high at 13% for 12-17 months old and 8% for 18-23 months old.

- Going without food for an entire day during this critical period of a child’s development is a cause for concern.

- Ideal vs Prevalent:

- The World Health Organization (WHO) suggests that at six months of age, 33% of a child’s daily calorie intake should come from food.

- This percentage increases to 61% by the time the child reaches 12 months of age.

- These recommended calorie percentages are the minimum amounts that a child should be receiving from food.

- Breast milk is an important source of nutrition for young children, and when a child cannot receive breast milk when needed, the percentage of food-sourced calories becomes even more critical.

- However, the current calorie intake in India is observed to be way lower than the suggested percentage.

- Deprivation of Specific Food Groups:

- Specific food group deprivations underlying the overall statistic of an estimated 60 lakh zero-food children in India, who are not getting to eat every day is also a concern.

- The deprivation is not just about the absence of any food, but also about the lack of access to specific food groups that are essential for healthy growth and development.

- More than 80% of children in the 6-23 months age group had not consumed any protein-rich foods for an entire day.

- This may contribute to the high prevalence of zero-food children in India.

- Close to 40% of children in the 6-23 months age group did not consume any grains (roti, rice, etc) for an entire day, while six out of 10 children do not consume any form of milk or dairy every day (zero-milk).

- Rising Burden of NCDs: To address the rising burden of non-communicable diseases, particularly among the middle class, a national effort to establish routine dietary and nutritional assessments for the entire population is the need of the hour.

- Urgent Action for better health outcomes:

- Access to adequate and affordable nutritious food for mothers is necessary for healthy breastfeeding, which is a crucial source of nutrition for young children.

- The current focus on referring to food intake among young children as “complementary” may not be sufficient in addressing the issue of food insecurity among this vulnerable population.

- Therefore, there is an urgent need to prioritize food intake among young children and elevate it to a primary importance in policies and guidelines related to maternal, infant, and young child nutrition.

- Deploying Comprehensive instead of Anthropometric Measures:

- Using anthropometric measures such as stunting or wasting to assess the extent of nutritional deprivation among young children in India has its own limitations as these measures are only proxies for overall deficiencies in the child’s environment and do not provide specific information on the nature of the deficiencies.

- It is important to note that the multi-factorial nature of the causes of stunting or wasting, makes it challenging for any single ministry to take responsibility for designing, implementing, and monitoring policies to reduce undernutrition among children.

- Assessments using household-level food insecurity modules developed by the Food and Agriculture Organization can be adapted to measure the extent of food insecurity among Indian households.

- Therefore, a more comprehensive and coordinated approach is needed to address the problem of undernutrition among young children in India with the involvement of multiple government ministries and departments, as well as other stakeholders such as civil society organisations and the private sector.

- Plugging the Food Production-Consumption Gap:

- India has seen notable success in various production metrics for food items, including becoming the world’s leading country in milk production.

- Despite these achievements, not being able to feed its own population indicates that achieving self-sufficiency in food production does not necessarily translate into food security for the population.

- This suggests that there are significant gaps between food production and consumption that need to be addressed to ensure adequate and nutritious food for all, particularly for vulnerable groups such as young children.

Way Forward: India faces a significant challenge in achieving the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 2 of ending hunger and ensuring access to safe and nutritious food for all by 2030.

- Mission Poshan 2.0: This flagship programme dedicated to maternal and child nutrition, has evolved in the right direction by targeting SDG 2 “zero hunger” and focusing on food-based initiatives, including its flagship supplementary nutrition programme service as mandated by the 2013 National Food Security Act.

- However, to effectively monitor and assess the performance of Poshan 2.0, there is an immediate need to develop appropriate food-based metrics.

- Drawing from the success of the Swachh Bharat Mission, which increased access to improved toilets among Indian households (from 48 per cent to 70 per cent between 2016 and 2021), Poshan 2.0 can use directly trackable metrics and strong political commitment to achieve its objectives.

- Strategic Initiatives: India, in line with the SDG of zero hunger, can take a strategic initiative led by the Prime Minister’s Office to eliminate food insecurity and ensure affordable access to sufficient and diverse nutritious food, with a special focus on young children.

- This initiative can build upon existing programs like Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana.

- Lessons from the 1st world countries: India can learn from the first world countries such as the US that has prioritized ending hunger by 2030 by launching an initiative to address hunger, nutrition, and health.

Beyond the Editorial

Measures to tackle the Challenge of Food Insecurity:

- Improving soil health: India needs to adopt sustainable farming practices and promote soil conservation to improve soil health. This can be done through the promotion of organic farming, use of bio-fertilizers, crop rotation, and reducing the use of chemical fertilizers.

- Boosting crop diversification: India needs to diversify its crop production and promote the cultivation of crops that are more resilient to weather changes, pests and diseases. This can include the promotion of drought-resistant crops, improved seed varieties, and agro-forestry.

- Strengthening food distribution systems: India needs to address the inefficiencies in its food distribution systems to ensure that food reaches the most vulnerable populations. This can be done through the adoption of technology such as digital ration cards, and the strengthening of grievance redressal and social audit mechanisms.

- Improving procurement: India needs to ensure that farmers get a fair price for their produce, and encourage them to grow crops that are in demand. This can be done through the provision of better market information, direct procurement from farmers, and encouraging crop diversification.

- Mitigating the impact of climate change: India needs to take measures to mitigate the impact of climate change on agriculture, such as promoting the use of water-efficient irrigation techniques, promoting agro-forestry, and developing drought-resistant crops.

- Strengthening global partnerships: India needs to strengthen its partnerships with other countries to ensure food security. This can include the sharing of best practices, investment in research and development, and support for smallholder farmers.

Article 142 of Indian Constitution, Sign...

Article 142 of Indian Constitution, Sign...

Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir (PoK): History...

Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir (PoK): History...

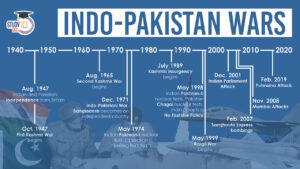

List of Indo-Pakistan Wars and Conflicts...

List of Indo-Pakistan Wars and Conflicts...