Table of Contents

Context: The article is discussing the limitations of the Rajasthan Right to Health (RTH) Act as a model for other states to follow. Despite objections from some doctors and criticisms of ambiguous definitions in the Act, the article argues that the Act is a moderate one that has far-reaching implications for public health. It suggests that legal pronouncements should be carefully drafted to pre-empt opposition, and that governments and the medical community should be sensitized to the broader social dimensions of health and health legislation. Finally, the article warns that radical pieces of legislation should not be pursued without adequate financial preparedness, as the obligation to provide healthcare is that of the state and not solely the responsibility of healthcare providers.

Diagnostic Imaging of the Rajasthan Right to Health Act Background

Right to Health Bill:

The Rajasthan Assembly recently passed ‘the Right to Health Bill’ despite protests by private doctors, making it the only state in India to legislate on the right to health.

Key provisions the Rajasthan’s Right to health bill

- Right to health: The Bill provides the right to health and access to healthcare for people in the state. This includes free health care services at any clinical establishment to residents of the state.

- Obligations of state government: The Bill sets certain obligations on the state government to ensure the right to health and maintain public health.

- Health authorities: Health Authorities will be set up at the state and district level. These bodies will formulate, implement, monitor, and develop mechanisms for quality healthcare and management of public health emergencies.

What is Right to Health (RTH)?

- Understanding health as a human right creates a legal obligation on states to ensure access to timely, acceptable, and affordable health care of appropriate quality.

- This includes safe and potable water, sanitation, food, housing, health-related information and education, and gender equality.

- The right to health includes both freedoms and entitlements:

- Freedoms: include the right to control one’s health and body (for example, sexual and reproductive rights) and to be free from interference (for example, free from torture and non-consensual medical treatment and experimentation).

- Entitlements: include the right to a system of health protection that gives everyone an equal opportunity to enjoy the highest attainable level of health.

Core Components of RTH:

- Right to health under international law:

- The right to health was first articulated in the WHO Constitution (1946) which states that: “the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being…”.

- The 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights mentioned health as part of the right to an adequate standard of living (article 25).

- It was again recognized as a human right in 1966 in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

- Global overview of RTH: More than half of the world’s countries including Uruguay, Latvia, and Senegal have some degree of a guaranteed, specific right to public health and medical care for their citizens written into their national constitutions.

- Right to health (RTH) in India:

- The Constitution of India does not expressly guarantee a fundamental RTH.

- The Supreme Court of India in Bandhua Mukti Morcha v Union of India & Ors, 1984 interpreted the RTH under Article 21 which guarantees the right to life.

- There are multiple references in the Constitution to public health and on the role of the State in the provision of healthcare to citizens:

- Article 39 (E): Directs the state to secure the health of workers.

- Article 42: Direct the state to provide just and humane conditions of work and maternity relief.

- Article 47: Casts a duty on the state to raise the nutrition levels and standard of living of people and to improve public health.

- Article 243G: It endows the Panchayats to strengthen public health.

Challenges in providing RTH in India:

- Low healthcare spending: Overall, India’s public health expenditure has remained less than 2% of the GDP.

- Suboptimal capacity:

- Every doctor in India caters to at least 1,511 against WHO’s recommendations of one doctor for every 1,000 people.

- Nurse-to-population ratio is 1:670 against the WHO norm of 1:300. Also, there are only 0.5 beds for every 1,000 people.

- Weak Primary health care (PHC) sector: Declaration of Alma-Ata, 1978 identified PHC as the key to the attainment of the goal of Health for All.

- 60% of PHCs in India have only one doctor while about 5% have none. This adversely impacts filtering of patients as well as prevention and early detection.

- Non availability of skilled workforce: India currently needs an additional 6.4 million healthcare resources (overall) to serve its population.

- Regional disparity: About 70% of the Indian population lives in rural areas. However, about 80 percent of doctors, 75 percent of dispensaries and 60 percent of hospitals are present in urban areas.

- Poor governance: The public sector offers healthcare at low or no cost but is perceived as being unreliable, of indifferent quality and generally is not the first choice, unless one cannot afford private care.

Initiatives to achieve RTH in India

- In 2019, a High-Level Group on the health sector constituted under the 15th Finance Commission had recommended that the right to health be declared a fundamental right.

- It also put forward a recommendation to shift the subject of health from the State List to the Concurrent List.

- National Health Policy (2017) provides for Universal Health Coverage for which Ayushman Bharat was launched in 2018.

- Mental Healthcare Act 2017 to provide for mental healthcare and services for persons with mental illness.

Decoding the Editorial

The article discusses the Rajasthan Right to Health (RTH) Act that has been a topic of controversy since it became law in the recent past, with some doctors calling it draconian and others supporting it. It suggests that there are certain aspects of the Act that have not been discussed enough, which make it unsuitable as a model for other states to follow.

- Need for Review:

- A review of the two iterations of the Rajasthan Right to Health (RTH) Bill can provide a good starting point for analysis.

- The primary iteration of the Bill was sent for review to a select committee in 2022.

- The committee made some amendments, and the amended version of the Bill was passed on March 21, 2023, which resulted in protests.

- It is opposed because of the fact that despite the review of the two iterations of the Bill, the amended version, which caused the controversy, was strongly influenced by the interests of the medical community.

- Amendments made to the Bill:

- Included Definitions: Following the select committee amendments, some definitions (accidental emergency, emergency care, and first aid), were added to the Bill.

- In addition, the term ‘designated health care centres’ was introduced, and a reimbursement clause for unpaid emergency care was added.

- While some changes were positive, most of the other changes were not beneficial for public health interests.

- Reduced Representatives: The composition of the State and district health authorities were restructured in the amended Bill.

- The initial iteration included representatives from alternative medical systems as ex-officio members, while the amended version reduced this to only one representative and replaced the others with medical education representatives.

- Additionally, the amended version swapped out public health/hospital management experts for Indian Medical Association (IMA) representatives as nominated members.

- This leaves the authorities without sufficient representation from the public health community and the community for which the Act is intended to benefit.

- Grievance Redressal System:

- The amended version of the Bill significantly limited the powers of the administration organs compared to the initial iteration of the bill.

- Additionally, the grievance redress system proposed in the initial iteration, which would have been handled through web portals, helpline centres, and officers concerned within 24 hours, was significantly altered in the amended bill.

- Under the new provisions, patient grievances will now be handled by the very health-care institution in question within three days, creating conflicts of interest and increasing the administrative burden of hospitals.

- This change could lead to patient grievances being handled poorly and informally, rather than being addressed properly and efficiently.

- Included Definitions: Following the select committee amendments, some definitions (accidental emergency, emergency care, and first aid), were added to the Bill.

- Challenges:

- The article suggests that Rajasthan Right to Health Act, which lacks public health representation, is not capable of achieving the goal of health legislation that includes not only curative medical care but also health promotion, disease prevention, and social determinants such as nutrition.

- The memorandum of understanding added to the Bill to make it acceptable to doctor associations excluded private multispecialty hospitals with less than 50 beds and those that did not avail of concessions or subsidized land/buildings from the government, effectively leaving out a large number of small and medium hospitals.

- This is in contrast to the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) in the U.S., which covers 98% of hospitals and ensures public access to emergency care.

- The article suggests that the exclusions in the Rajasthan Right to Health Act make it unsuitable as a template for other states or pan-India legislation.

Beyond the Editorial

The government should take several steps to move forward with health legislation.

- Firstly, legal pronouncements should be drafted meticulously to prevent opposition from arising in the first place.

- Secondly, the government should not be swayed by organised medical interests alone and should keep in mind the broader social dimensions of health and health legislation.

- Thirdly, the government should sensitise itself to the fact that private medical practice cannot be as laissez-faire as possible if equitable, universal health care is to be achieved.

- Finally, the government should ensure that it has enough financial preparedness before implementing radical pieces of legislation, as it is the government’s obligation to provide health care and not that of health-care providers.

- A legislatively guaranteed right will make access to health legally binding and ensure accountability.

- A constitutional amendment on the lines of the 93rd Amendment to the Constitution which provided a constitutional sanction to the right to education, should be adopted for providing adequate healthcare in India.

- In addition to statutory recognition, the right to health in India will need to be implemented within the framework of principles of solidarity, proportionality, and transparency that are central to international human rights and health law.

SSC CGL Exam 2025 Apply Online Starts Ap...

SSC CGL Exam 2025 Apply Online Starts Ap...

Daily Quiz 19 April 2025

Daily Quiz 19 April 2025

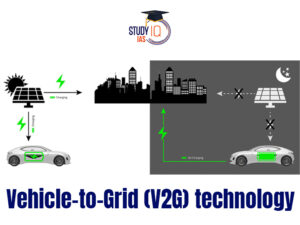

Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G) Technology and its...

Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G) Technology and its...