Table of Contents

Context: The Supreme Court has stayed Rahul Gandhi’s conviction in a defamation case by a Gujarat court in which he has been sentenced to two years in prison.

About the Anti-Defection Law

- The Anti-Defection Law in India refers to a set of constitutional provisions enacted to prevent political defections by elected representatives.

- The law aims to maintain stability in the democratic system by discouraging elected officials from switching parties after being elected.

- It was first introduced through the 52nd Amendment Act of 1985 and is enshrined in the Tenth Schedule of the Indian Constitution.

What is ‘Defection’?

- The term ‘Defection’ has been derived from a Latin word ‘Defectio’ which means to abandon a position or association, often to join an opposing group.

- Defection covers the change of party affiliation both from the opposition to the government side or vice versa as also change as between the parties on the side of the house.

- Traditionally this phenomenon was known as ‘floor crossing’ which had its roots in the British House of Commons, where the legislator could change his allegiance when he crossed the floor and moved from the side of the government to the side of the opposition or vice-versa as the case may be.

History behind the Anti-Defection Law

- The phenomenon of defection despite the fact that it was acute became apparent after the fourth general election in 1967.

- Up to 1967 the cases of defection were 400 which subsequently rose to a figure of 500 odd cases of defection, in which 118 were by the Ministers or Ministers of State.

- Aaya Ram Gaya Ram was a phrase that became popular in Indian politics after a Haryana MLA Gaya Lal changed his party thrice within the same day in 1967.

- Therefore, in 1967, a committee was formed to deal with the issue of defection. There were several recommendations made by the committee on defection.

- Those recommendations were considered and were introduced in the form of a bill in 1973 that was later passed as Anti Defection law in 1985.

Key Provisions under the Anti-Defection Law

The Anti-Defection Law (or the Tenth Schedule) includes the following provisions with regard to the disqualification of MPs and MLAs on the grounds of defection:

| Grounds for disqualification |

|

| Power to disqualify |

|

| Exceptions under the Anti Defection Law |

|

| Scope for Judicial Review |

|

Advantages of Anti-Defection Law

- Prevents Political Instability: Defections can lead to political instability, as governments may lose their majority and struggle to function effectively. The Anti-Defection Law prevents such situations by discouraging elected representatives from defecting or switching parties.

- Upholds Party Discipline: The law encourages party discipline among elected representatives. It emphasizes that elected members should adhere to the policies, principles, and ideologies of their respective political parties.

- Safeguards Public Mandate: The Anti-Defection Law protects the interests of the electorate by ensuring that the elected representatives do not betray the trust of voters. When citizens vote for a candidate, they do so based on the party’s agenda and the promises made during elections.

Disadvantages of Anti-Defection Law

- Limited Freedom of Speech: Members being forced to obey party whips restricts their freedom of expression and goes against the principle of representative democracy.

- Reduced Accountability: By preventing parliamentarians from changing their allegiance or voicing dissent, the law limits their ability to hold the government accountable for its actions.

- Potential Misuse: There is a risk of the Anti-Defection Law being misused by political parties or leaders for their own advantage. They may use the threat of disqualification or other punitive measures to suppress dissent within their party or to force compliance with party decisions, even if they are against the best interests of the public or the elected representatives.

- Other challenges with the Anti-defection Law:

- Time Limit for Presiding Officer: The lack of a specified time-period for the Presiding Officer to decide on a disqualification plea leads to unnecessary delays, allowing defected members to continue in their positions while still being part of their original parties.

- Ambiguous Nature of Split: The ambiguity arises when MLAs defect in small groups to join the ruling party, and it is unclear whether they will face disqualification if the Presiding Officer’s decision is made after a significant number of opposition members have already defected.

- Defecting to party forming Government after election: Winning candidates resigning from their elected party immediately after election results and joining the party that forms the government raises concerns of fraud and goes against the democratic spirit.

- Power to the Speaker: Granting the Speaker the power to make decisions on disqualification raises criticism regarding their legal knowledge and expertise to handle such cases impartially.

- Problem with merger provision: The provision focuses on the number of members involved in a merger rather than the underlying reasons for defection, potentially allowing for opportunistic and questionable mergers to escape disqualification.

Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir (PoK): History...

Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir (PoK): History...

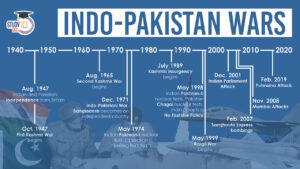

List of Indo-Pakistan Wars and Conflicts...

List of Indo-Pakistan Wars and Conflicts...

Daily Quiz 24 April 2025

Daily Quiz 24 April 2025