Table of Contents

Context: According to a recent study, a strip of the Pacific Ocean seabed which was mined over 40 years ago (1979) has still not recovered.

About Deep Sea Mining

The deep sea is broadly defined as the ocean depth where light begins to fade, at an approximate depth of 200 metres or the point of transition from continental shelves to continental slopes.

Deep Sea mining refers to the extraction of mineral deposits and metals from the ocean floor. There are three types:

- Polymetallic Nodule Mining: Collecting metal-rich nodules from the seabed.

- Seafloor Sulphide Mining: Extracting sulphide deposits from hydrothermal vents.

- Cobalt Crust Mining: Stripping cobalt-rich crusts from underwater rocks.

Features of deep sea

- The deep sea is characterized by extremely high pressure, low temperatures, and darkness.

- Some of the notable features of the deep sea include underwater mountains and ridges, vast plains and canyons, hydrothermal vents, and cold seeps.

Deep sea minerals

They are minerals that are found on the ocean floor, specifically in the deeper parts of the ocean, beyond the continental shelf.

- Polymetallic nodules: These are small, rounded lumps of minerals that are found on the seafloor, usually on abyssal plains. They are composed of manganese, iron, nickel, copper, and cobalt.

- Seafloor massive sulfides (SMS): They form around hydrothermal vents, where hot, mineral-rich fluids are released from the seafloor. SMS deposits are composed of copper, gold, silver, zinc, and other metals.

- Cobalt-rich crusts: They form on the seafloor, typically on seamounts and other volcanic features. They are composed of cobalt, nickel, iron, manganese, and other metals.

Need for deep sea minerals

Depleting terrestrial deposits and rising demand for metals are stimulating interest in the deep sea, with a focus on commercial mining.

Who authorizes deep sea mining?

The International Seabed Authority (ISA) is responsible for organizing, regulating, and controlling all mineral-related activities in the international seabed area beyond the limits of national jurisdiction.

- ISA is an intergovernmental organization that was established by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) in 1994.

- More than 30 exploration licenses have been issued so far, with activity mostly focused in an area called the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone, which spans 1.7 million square miles (4.5 million square kilometres) between Hawaii and Mexico.

Why is It Important?

- These deposits contain nickel, rare earth elements, and cobalt which are essential for renewable energy technologies, batteries and consumer electronics (e.g., cell phones, and computers).

- As onshore reserves decline, companies and governments consider deep-sea mining a strategic resource.

Need for Deep Sea Mining

Critical Minerals

The deep sea contains three primary sources for mining critical minerals:

- Potato-size manganese nodules (rich in manganese, cobalt, copper, nickel, and rare earth elements);

- Deposits of sulfur-containing minerals around underwater openings known as hydrothermal vents; and

- Cobalt-rich crusts line the sides of mid-ocean ridges and underwater mountains, also known as seamounts.

Facilitate Energy Transition

Copper or nickel for batteries, cobalt for electric cars or manganese for steel production: rare earth minerals and metals are fundamental to the renewable energy technologies driving the world’s energy transition.

- These are key to making modern gadgets, from smartphones and laptops to pacemakers, hybrid cars and solar panels. Carmakers will need more of these metals in order to make battery cathodes and electrical connectors for an electric vehicle fleet.

Depleting Terrestrial Deposits

Expanding technology and infrastructure have fueled the global demand for resources like cobalt and nickel, whose supply is depleting fast onshore. Hence, more and more countries, including manufacturing powerhouses India and China, are moving towards the ocean to extract these resources.

Potential Zones

The Clarion-Clipperton Zone between Hawaii and Mexico is a potential hotbed for critical minerals. The basin in the central Indian Ocean and the seabed off the Cook Islands, Kiribati atolls and French Polynesia in the South Pacific are also of interest for potential extraction.

Impacts of Deep Sea Mining

Physical Destruction of the Seabed

- Mining strips away the top layers of the seabed, removing valuable ecosystems.

- Permanent habitat destruction for organisms dependent on deep-sea sediments.

Impact on Marine Biodiversity

- Reduction in marine life: Many species, including deep-sea corals, sponges and bottom-dwelling organisms, struggle to survive.

Noise, Vibration, and Light Pollution

- Deep-sea mining operations generate loud noise and vibrations, disrupting marine communication (whales, fish and other species).

- Artificial lighting in deep-sea environments affects nocturnal species and their natural behaviours.

Chemical Pollution and Toxic Waste

- Mining releases heavy metals like mercury, lead, and arsenic, contaminating water and marine food chains.

- Waste disposal from mining increases ocean acidification, affecting coral reefs and marine biodiversity.

Climate Change Implications

- The deep sea acts as a carbon sink, storing huge amounts of carbon.

- Mining disturbs these sediments, potentially releasing stored carbon dioxide, and contributing to climate change.

Concerns and Effects of Deep Sea Mining

Noise pollution

- If allowed, commercial-scale mining is expected to operate 24 hours a day, causing noise pollution.

- The mining noise can overlap with the frequencies at which cetaceans communicate, which can cause auditory masking and behaviour change in marine mammals, the analysis said.

Sediment plumes

- Deep-sea mining will stir up fine sediments on the seafloor consisting of silt, clay and the remains of microorganisms, creating plumes of suspended particles.

- Settlement of sediment plumes generated by mining vehicles could smother the species at the bottom of the ocean, or benthic species, in the vicinity.

Habitat destruction

- Deep Sea mining operations can physically disturb seafloor habitats, destroying or altering critical habitats for deep sea species, including corals, sponges, and other organisms.

Disturbance of the Seafloor

- The digging and gauging of the ocean floor by machines can alter or destroy deep-sea habitats. This leads to the loss of species, many of which are found nowhere else, and the fragmentation or loss of ecosystem structure and function.

Loss of Undiscovered Species

- The deep sea is home to unique species that have adapted themselves to conditions such as poor oxygen and sunlight, high pressure and extremely low temperatures. Such mining expeditions can make them go extinct even before they are known to science.

Disruption of deep-sea carbon storage

- The deep sea plays an important role in storing carbon, and mining activities could potentially disrupt this process, releasing large amounts of carbon into the atmosphere and contributing to climate change.

Lack of Research in Deep Sea

- The deep sea remains understudied and poorly understood, there are many gaps in the understanding of its biodiversity and ecosystems.

- This makes it difficult to assess the potential impacts of deep-sea mining or to put in place adequate safeguards to protect the marine environment, and people whose livelihoods depend on marine and coastal biodiversity.

India’s Quest Towards Deep Sea

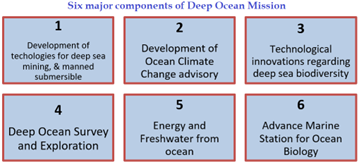

Deep ocean mission

- In 2021, the Union Cabinet has approved the ‘deep ocean mission’ with an outlay of Rs. 4077 crores for a period of 5 years.

- In the Union Budget 2023-24, the government has further allocated Rs 600 crore for the deep ocean mission.

India and Polymetallic Nodules

- India signed a 15-year contract for the exploration of Polymetallic Nodules in the Central Indian Ocean Basin (CIOB) with the International Seabed Authority in 2002.

- In 2016, India got an extension of this contract up to 2022.

Samudrayaan Mission

It is India’s first unique manned ocean mission that aims to send men into the deep sea in a submersible vehicle for deep-ocean exploration and mining of rare minerals.

- It will send three persons in a manned submersible vehicle MATSYA 6000 to a depth of 6000 metres into the sea for deep underwater studies.

- With this Unique Ocean Mission, India joined the elite club of nations such as the US, Russia, France, Japan, and China to have niche technology and vehicles to carry out subsea activities.

Way Forward

- At the IUCN World Conservation Congress in Marseille (2021), IUCN Members adopted Resolution 122 to protect deep-ocean ecosystems and biodiversity through a moratorium on deep-sea mining unless and until a number of conditions are met. These include:

- The risks of mining are comprehensively understood, and effective protection can be ensured.

- Rigorous and transparent impact assessments are conducted based on comprehensive baseline studies.

- The Precautionary Principle and the ‘Polluter Pays Principle’ are implemented.

- Policies incorporating circular economic principles to reuse and recycle minerals have been developed and implemented.

- The public is consulted throughout decision-making.

- The governance of deep-sea mining is transparent, accountable, inclusive, effective and environmentally responsible.

- Reliance on metals from mining can be reduced by redesigning, reusing and recycling.

- Research should focus on creating more sustainable alternatives to their use because deep-sea mining could irreparably harm marine ecosystems and limit the many benefits the deep sea provides to humanity.

- The mining code should be adopted soon so that deep-sea mining applications can be adjudicated around robust rules that protect the environment.

Places in News for UPSC 2025 for Prelims...

Places in News for UPSC 2025 for Prelims...

Iron Ore, Types, Uses, Distribution in I...

Iron Ore, Types, Uses, Distribution in I...

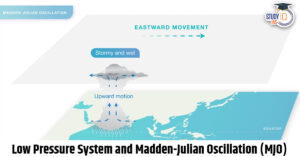

Low Pressure System and Madden-Julian Os...

Low Pressure System and Madden-Julian Os...