Table of Contents

The 29th Conference of the Parties (COP29) to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) will take place in Baku, Azerbaijan, from November 11 to 22, 2024. This conference is anticipated to focus heavily on climate finance, with significant discussions surrounding the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) for climate finance post-2025.

Vulnerability of Developing States

- Economically developing countries are among the most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change.

- This vulnerability arises from:

- Geographical Factors: Many developing nations are located in regions that are particularly susceptible to climate-related disasters.

- Economic Dependencies: Their economies often rely on sectors like agriculture, which are highly sensitive to climate variations.

- Despite their vulnerability, developing countries have contributed minimally to global emissions.

- The Sixth Assessment Report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) indicates that developed nations account for 57% of cumulative global emissions since 1850, despite having smaller populations than many developing countries.

What is Climate Finance?

- According to the UNFCCC, climate finance refers to “local, national, or transnational financing — drawn from public, private, and alternative sources — that seeks to support mitigation and adaptation actions addressing climate change.”

- Climate finance can come from:

- Sources: Public or private, and can be domestic or international.

- Uses: Mitigation (reducing emissions) or adaptation (adapting to climate impacts).

- A basic milestone for climate finance was the Copenhagen Agreement (2009 at COP15).

- In the agreement, developed countries pledged 30 billion dollars between 2010 and 2012 for developing countries to carry out mitigation and adaptation activities, and 10 billion dollars per year until 2020.

- This commitment was reiterated in the Paris Agreement in 2015, extending this aid until 2025.

- The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) tracks these financial flows, which include:

- International Public Finance: Comprising commercial and concessional loans, grants, and equity.

- Private finance is mobilised by public finance.

- In 2022, loans constituted 69.4%, while grants made up 28% of international public climate finance.

- However, criticisms have emerged regarding the OECD’s reporting methods.

- Developing countries argue that these reports should reflect actual disbursals rather than mere commitments and emphasise that only new and additional funds should be counted.

|

Definition |

|

Need for Climate Finance in Developing Countries

Developing countries require external financing for climate action due to:

- Higher costs of capital, such as for solar photovoltaic and storage technologies, which can be twice as high in developing nations compared to developed ones.

- According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), 675 million people in developing countries lacked access to electricity in 2021.

Specific Financial Needs

India exemplifies the financial requirements for climate action:

- By 2030, India aims to:

- Install 500 GW of non-fossil-fuel energy capacity.

- Produce 5 million metric tonnes of green hydrogen annually.

- Expand electric vehicle (EV) adoption.

- Estimated financial needs by 2030:

- ₹16.8 lakh crore for achieving 450 GW of renewable energy capacity.

- ₹8 lakh crore for the Green Hydrogen Mission.

- Consumers will need to spend ₹16 lakh crore on EVs.

- To achieve net-zero emissions by 2070, India will require ₹850 lakh crore in investments.

New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG)

The upcoming 2024 UN Climate Conference (COP29) is tasked with forging an agreement to establish a new collective quantified goal (NCQG) to provide needed climate finance.

- Key considerations include:

- Actual disbursals rather than just commitments.

- Funds must be new and additional.

- Emphasis on public capital in the form of direct grants.

- Private capital mobilised by public funding should be included, but organically flowing private finance should not be counted.

- An independent expert group has estimated that developing countries (excluding China) will require approximately $1 trillion in external finance by 2030.

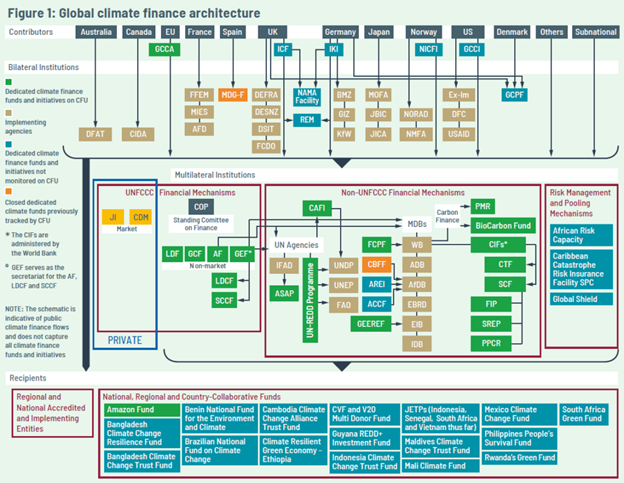

Global Architecture of Climate Finance

The global architecture of climate finance is complex and multifaceted, involving a variety of funds and mechanisms designed to facilitate the flow of financial resources for climate-related projects.

Key components include:

- Multilateral Climate Funds: These are governed by multiple countries and include:

- Clean Development Mechanism (CDM): Part of the Kyoto Protocol, the CDM enables developed countries to invest in projects that reduce emissions in developing countries and earn carbon credits in return.

- Joint Implementation (JI): Another Kyoto Protocol mechanism that allows developed countries to earn emission reduction credits by investing in emission reduction projects in other developed countries.

- Global Environment Facility (GEF): Set up in 1992, the GEF serves as a financial mechanism for several conventions, including the UNFCCC.

- It provides grants for projects related to biodiversity, climate change, land degradation, international waters, and the ozone layer.

- Green Climate Fund (GCF): Established within the framework of the UNFCCC, the GCF assists developing countries in adaptation and mitigation practices to counter climate change.

- Adaptation Fund: Funded primarily by a share of proceeds from CDM project activities, it finances projects and programs that help vulnerable communities in developing countries adapt to climate change.

- Standing Committee on Finance (SCF): Created to assist the COP in the UNFCCC with aspects of the financial mechanism, the SCF helps in rationalising, mobilising, and accessing financial resources.

- Climate Investment Funds (CIFs): Administered by the World Bank, these funds provide middle-income countries with scaled-up financing to initiate transformational change towards sustainable development.

- Bilateral and Regional Initiatives: Countries often engage in direct funding agreements, such as those through USAID or the European Union’s Global Climate Change Alliance.

- National Climate Funds: Many countries have established their own funds to align international contributions with national priorities, enhancing coordination in financing efforts.

| Important Agreements in Climate Finance |

Several key international agreements have shaped the landscape of climate finance:

India’s Initiatives in Climate Financing:India, as a developing country with significant vulnerability to climate change and an emerging economy, has put in place a range of initiatives to finance its climate change strategies:

|

Historical Challenges with Climate Finance

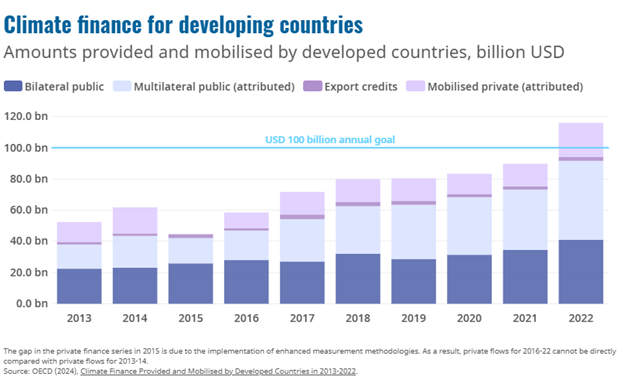

- The $100 Billion Commitment:

- The $100 billion annual climate finance pledge, was initially set in 2009 and extended to 2025.

- Developed countries failed to meet the original 2020 deadline but finally met the target in 2022 by mobilising $115.9 billion.

- The missed deadline created mistrust, as developing countries faced worsened impacts from climate delays.

- The target itself is inadequate—current estimates from the Standing Committee on Finance indicate the actual cost needs range between $5.036 trillion and $6.876 trillion for 48% of the needs identified by 98 parties.

- Private vs. Public Finance: The current climate finance model has led to an over-reliance on loans rather than grants, increasing debt burdens for vulnerable countries. The funding landscape displays a bias toward mitigation projects over adaptation efforts, leaving critical areas like infrastructure resilience and disaster management underfunded.

- g., Currently, 69% of all climate finance is provided in loans.

- Access Barriers to Climate Funds: Funds like the Green Climate Fund (GCF) and the Global Environment Facility (GEF) remain challenging to access due to procedural hurdles, slowing adaptation progress in developing nations.

- Flaw in Definition: The Standing Committee on Finance definition of climate finance lacks explicit references to additionality—whether funds are new or incremental—which raises concerns about accountability.

- Debate on Expanding Contributor’s Base: Switzerland and Canada propose that additional contributors be determined by emissions and GNI per capita, which would bring countries like China and oil-producing nations (e.g., Saudi Arabia, and Qatar) into the funding pool.

- Developing nations argue that this shift threatens principles of equity and common but differentiated responsibilities, which are fundamental to the Paris Agreement.

Future Directions

- Need for Technology Transfer: Developing countries require not only financial support but also technology transfer and capacity building.

- Trust and Accountability: The success of NCQG negotiations will depend on restoring trust between developed and developing nations while addressing historical responsibilities.

- Critical Questions: The negotiations must determine whether they will lead to just outcomes or merely promises without substantial commitments.

- Standardised Definitions and Reporting: Developing a global consensus on what constitutes climate finance and establishing robust reporting frameworks would provide clarity and transparency.

- Investment vs. Finance: Climate finance should prioritise public funds directed from developed to developing countries. Counting private investments could dilute developed countries’ accountability, as private funding lacks the public oversight needed for effective climate adaptation.

Ramsar Sites in India 2025 List: Names, ...

Ramsar Sites in India 2025 List: Names, ...

List of National Parks in India 2025, Ch...

List of National Parks in India 2025, Ch...

Bonnet Macaques: Habitat, Features, Beha...

Bonnet Macaques: Habitat, Features, Beha...