Table of Contents

Carnatic music, deeply rooted in the southern regions of India, boasts a sophisticated theoretical foundation centred around Ragam (Raga) and Thalam (Tala). Purandaradasa (1480-1564), revered as the father of Carnatic music, systematized its methods and authored numerous compositions, codifying the musical system. Venkat Mukhi Swami, a luminary, developed the classification system “Melankara” for South Indian ragas. In the 18th century, the Trinity—Thyagaraja, Shama Shastri, and Muthuswami Dikshitar—emerged, compiling compositions that define the Carnatic music repertoire, marking a pivotal period in its evolution. This classical tradition continues to enchant with its rich heritage and nuanced musical expressions.

We’re now on WhatsApp. Click to Join

Carnatic Music Origin

Carnatic music, one of the classical music traditions of India, has ancient roots that can be traced back over several centuries. The origin of Carnatic music is deeply embedded in the cultural and religious practices of the southern regions of India, particularly in present-day Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, and Kerala. While it’s challenging to pinpoint an exact date or origin, the development of Carnatic music can be understood through historical and cultural contexts.

Key factors in the origin and development of Carnatic Music include:

Ancient Scriptures and Traditions

- Carnatic music has strong ties to ancient Indian scriptures, particularly the Sama Veda, which is one of the four Vedas and contains hymns set to music. The musical elements in the Sama Veda laid the foundation for the intricate melodic and rhythmic structures found in Carnatic music.

Temple Traditions

- Temples played a significant role in the development and preservation of Carnatic music. Musical performances were integral to temple rituals, and the rich musical heritage was passed down through generations within the temple settings.

Bhakti Movement

- The Bhakti movement, which gained prominence between the 6th and 17th centuries, contributed to the development of devotional music. Saints and poets, known as Alwars and Nayanars in the Tamil tradition, composed devotional verses that later became part of the Carnatic music repertoire.

Influence of Medieval Composers

- During the medieval period, composers like Purandaradasa (15th-16th century) made significant contributions to the systematization and codification of Carnatic music. Purandaradasa is often considered the father of Carnatic music for his role in organizing the melodic and rhythmic aspects of the tradition.

Trinity of Carnatic Music

- The 18th century saw the emergence of three prolific composers—Thyagaraja, Shama Shastri, and Muthuswami Dikshitar, collectively known as the Trinity of Carnatic music. Their compositions further enriched the Carnatic music repertoire, and their contributions are considered foundational to the tradition.

Oral Tradition and Guru-Shishya Parampara

- Carnatic music has been primarily transmitted through an oral tradition, with knowledge passed down from guru to shishya (teacher to disciple). This guru-shishya parampara (teacher-disciple tradition) remains a fundamental aspect of learning and preserving Carnatic music.

The origin and evolution of Carnatic music are complex and multifaceted, influenced by religious, cultural, and historical developments over the centuries. The tradition continues to thrive as a classical art form with a rich and intricate musical heritage.

Key Aspects of Carnatic Music

Carnatic music is one of the classical music traditions of India, with its roots in the southern part of the country. It is one of the two main traditions of Indian classical music, the other being Hindustani music, which is prevalent in the northern part of India. Here are some key aspects of Carnatic music:

Raga (Melodic Framework)

- Definition: A raga is a melodic framework used in Indian classical music, providing a set of rules for building a melody. Each raga has specific ascending (Arohana) and descending (Avarohana) note patterns, defining its unique character.

- Emotion and Mood: Ragas are associated with specific moods, times of the day, and seasons. For example, the raga Bhairavi is often associated with devotion, and it is traditionally performed in the early morning.

Tala (Rhythmic Cycle)

- Definition: Tala refers to the rhythmic cycle or beat pattern in Carnatic music. It is a fundamental aspect that structures the temporal dimension of the music.

- Variety of Talas: There are numerous talas with varying numbers of beats, such as Adi Tala (8 beats), Rupaka Tala (6 beats), and Misra Chapu (7 beats). The rhythmic intricacies contribute to the dynamic nature of Carnatic performances.

Krithis and Varnams

- Krithis: These are longer and more complex compositions that include both lyrical and melodic elements. They often convey deep philosophical and devotional themes. The Trinity of Carnatic music—Tyagaraja, Muthuswami Dikshitar, and Shyama Shastri—composed numerous krithis.

- Varnams: Shorter compositions that serve as warm-ups or practice pieces. They are characterized by fast and intricate patterns, helping musicians develop technical proficiency.

Carnatic Instruments

- Veena and Violin: String instruments like the veena and violin are commonly used in Carnatic music. The violin, in particular, plays a crucial role in accompanying vocal performances.

- Mridangam and Ghatam: Percussion instruments like the mridangam (double-headed drum) and ghatam (clay pot) provide rhythmic support. The mridangam player has the challenging task of interpreting and enhancing the nuances of the melody through percussion.

Concert Structure

- Vocal Tradition: While instruments play a vital role, vocal music is considered the core of Carnatic tradition. Vocalists are trained to explore the full range of their voices, emphasizing expression and emotion.

- Concert Components: A typical concert includes a varnam as an opening piece, followed by various krithis in different ragas and talas. The artist may also present alapana (improvisation), neraval (elaboration of lyrical lines), and swara kalpana (melodic improvisation).

Guru-Shishya Parampara

- Oral Tradition: Carnatic music is traditionally passed down orally from guru to shishya. This direct, personal transmission allows for a deep connection between the teacher and the student, fostering a holistic understanding of the art.

Rasas (Emotions)

- Expressive Elements: Musicians aim to evoke specific emotions or rasas through their performances. The interaction between raga, tala, and expressive techniques such as gamakas (ornamentation) contributes to the emotional impact.

Great Composers

- Trinity of Carnatic Music: Tyagaraja, Muthuswami Dikshitar, and Shyama Shastri are revered as the Trinity of Carnatic music. Their compositions form the backbone of the repertoire, and musicians continue to interpret and present their works in diverse ways.

Carnatic music, with its rich heritage and intricate structure, is a profound art form that continues to captivate audiences around the world. The balance of melody, rhythm, and emotion creates a musical experience that transcends cultural boundaries.

Carnatic Music UPSC

Carnatic music, deeply rooted in southern India, has ancient origins intertwined with cultural, religious, and historical influences. Purandaradasa, the father of Carnatic music, systematized its methods, and the Trinity of Carnatic music—Thyagaraja, Shama Shastri, and Muthuswami Dikshitar—emerged in the 18th century, shaping its repertoire. This classical tradition revolves around the intricate concepts of Ragam and Thalam, with a rich theoretical foundation.

Ancient scriptures, temple traditions, the Bhakti movement, and the oral guru-shishya parampara played pivotal roles in its development. Carnatic music continues to enchant with its nuanced expressions, highlighting the harmonious blend of melody, rhythm, and emotion.

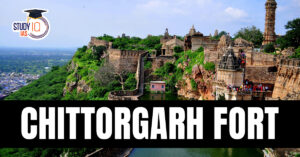

Chittorgarh Fort: Mining Ban within 10 k...

Chittorgarh Fort: Mining Ban within 10 k...

PM Modi visits Wat Pho Temple in Bangkok

PM Modi visits Wat Pho Temple in Bangkok

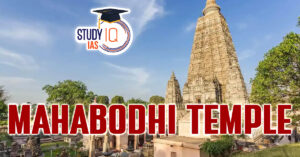

Mahabodhi Temple Complex at Bodh Gaya

Mahabodhi Temple Complex at Bodh Gaya