Table of Contents

Arts of the Mauryan Period

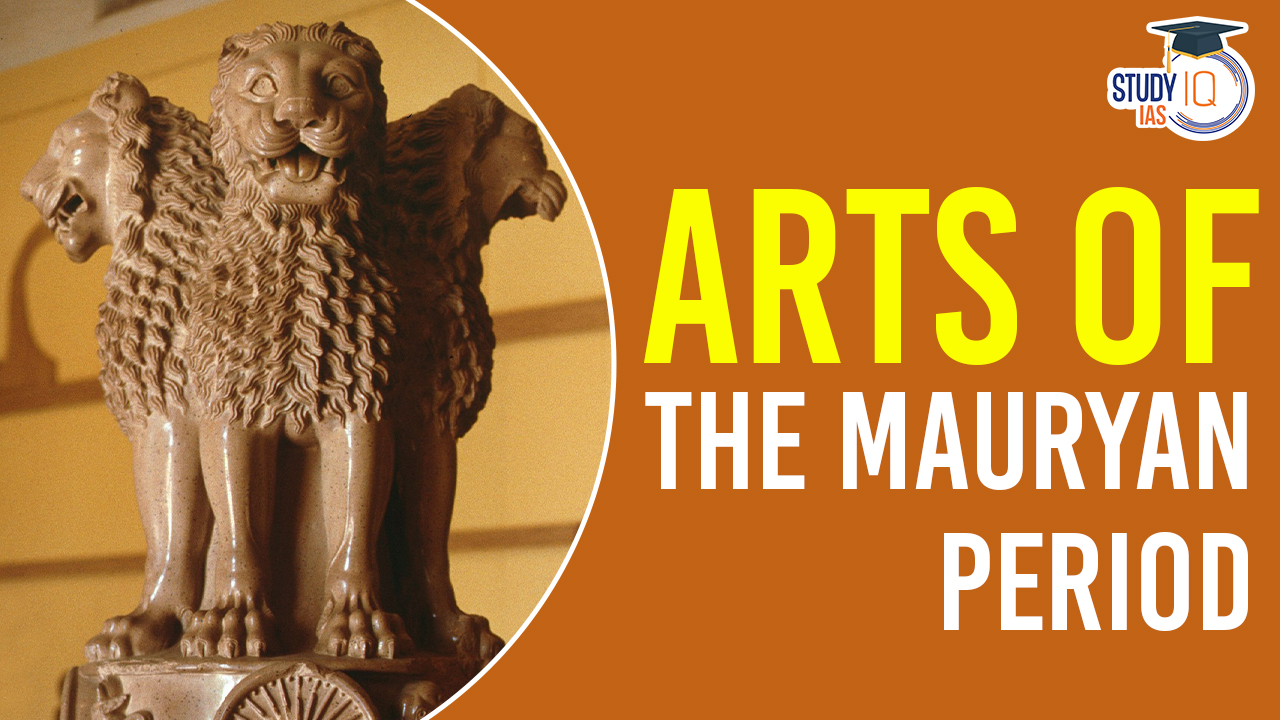

The fourth and second centuries were a golden age for Mauryan art and architecture. From 322 BCE to 185 BCE, the dynasty existed. The creation of pillars, stupas, and viharas was a distinctive feature of Mauryan art and architecture. Sandstone was used to create the pillars. It was a distinguishing element of Mauryan art and construction. They had written on them the decrees of Emperor Ashoka. The stupas were substantial dome-shaped buildings that served as Buddhist shrines. Buddhist monks lived in the viharas, which were residences. Sculpture played a major role in presenting Mauryan art. The evolution of stone carving art is notable for this time period.

Arts of the Mauryan Period Background

Religions of the Shramana tradition, including Jainism and Buddhism, emerged around the sixth century BCE. The Mauryas had become a significant political force by the fourth century BCE, and by the third century, they controlled a sizable portion of India. At the time, there were many other religious practises, such as the worship of mother goddesses and yakshas. Even so, Buddhism rose to become the most practised religion.

After the Harappan civilization, only the Mauryan period saw the development of enormous stone sculpture and structures. Different objectives were provided by pillars, sculptures, rock-cut architecture, and buildings like stupas, viharas, and chaityas. They exhibit excellent aesthetic qualities, as well as excellent design and execution.

Arts of the Mauryan Period and Their Types

Mauryan Pillars and Sculptures

Indian stone sculpture made a creative and magnificent advancement at this time; much of the earlier work, which was probably made of wood and is now lost, was likely constructed of stone. The exquisitely carved animal capitals that have been preserved from numerous of Ashoka’s pillars, especially the Lion Capital of Sarnath, which is now India’s National Emblem, are his best-known and greatest creations. While certain stone pieces and countless smaller terracotta works represent surviving popular art, the pillars and capitals depict court art.

Example: Lion Capital, Sarnath

- The Sarnath Lion Capital is the name given to the Lion Capital that was found more than a century ago at Sarnath, close to Varanasi.It was constructed by Ashoka in honour of “Dhammachakrapravartana,” or the Buddha’s first sermon, and is one of the finest specimens of sculpture from the Mauryan era.It was once composed of five parts:

- The shaft of the pillar.

- The base or lotus bell.

- An abacus-style drum with four animals moving clockwise around it at the foot of the bell.

- A representation of four regal addorsed (back to back) lions.

- Dharamchakra/Dharmachakra, the fifth component mentioned above, is the pillar’s crowning feature. It is a huge wheel. This wheel, though, is on display in the Sarnath site museum and is currently broken.

- The capital’s four Asiatic lions, which are seated back to back and have very defined facial muscles, stand for strength, courage, pride, and self-assurance.

- The sculpture’s surface is highly polished, as was customary during the Mauryan era.

- The abacus (drum on the bell base) depicts a chakra (wheel) in each of the four directions, with an animal (a bull, a horse, an elephant, or a lion) between each chakra.

- The circular abacus is supported by an inverted lotus capital, and the 24-spoke chakra is designed to resemble the Indian National Flag.

- The National Emblem of Independent India is the capital without a shaft, the lotus bell, and the crowning wheel.

- Only three Lions are visible in Madhav Sawhney’s chosen emblem; the fourth is hidden from view.

- A lion capital has also been discovered at Sanchi, albeit it is in poor shape, and is arranged so that only one chakra can be seen in the middle, with the bull on the right and the horse on the left.

- A pillar discovered at Vaishali faces north, the direction of the Buddha’s final journey.

Terracottas

The most prevalent Mauryan artworks are popular clay objects of all sizes that have been found at Mauryan sites and elsewhere. They are more numerous between Taxila and Pataliputra. Many of them have more refined technical skills, stylised shapes, and distinctive decorations. Although some appear to have been cast from moulds, repetition isn’t very common.

Among the Taxila terracotta are deity figurines, votive reliefs featuring deities, toys, dice, ornaments, and beads. Among the jewels were round medallions, which were reminiscent of the bullae worn by young Roman men. Folk gods and goddess figures made of terracotta are ubiquitous (some of them may even be dolls), and they have an earthy charm. Most of the animal figures are probably toys for kids.

Example: Didarganj Yakshi

- Didarganj near Patna’s life-size standing statue of a Yakshi holding a chauri (flywhisk) is another excellent example of the Mauryan period’s sculptural culture.

- It is a spherical, sandstone sculpture with a polished surface that is free-standing and tall proportioned.

- The image displays skill in the handling of form and media; the chauri is grasped in the right hand, while the left hand is fractured.

- The sculpture’s attention to the muscular, round body is apparent.

- The eyes, nose, and lips are sharp; the face is round with fat cheeks, and the neck is proportionately tiny.

- Muscle folds are accurately depicted.

- The belly is hanging from the full-round necklace beads.

- The cinching of clothing around the abdomen is done with considerable care.

- The lines sticking out from the legs reveal every fold of the clothing on the legs, giving the appearance of transparency.

- The feet are adorned with thick bell embellishments.

- Heavy breasts are a sign of body heaviness.

- The back is visible, and the hair is tied in a knot there.

- The image’s reverse displays further incised lines on the flywhisk in the right hand.

Mauryan Paintings

Megasthenes claims that the Mauryans had some magnificent paintings, but none of them have survived. The paintings of the Ajanta Caves, the earliest significant body of Indian art, show that there was an established tradition that may have originated during the Mauryan periods some years later.

Mauryan Pottery

Ceramics from the Mauryan era come in a wide variety of styles. The most sophisticated method, however, may be seen in a type of pottery known as Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW), which was well-liked in the earlier and early Mauryan times. It has a highly polished glaze finish that comes in a variety of colours, including metallic steel blue, deep grey, and jet black. There are occasionally little reddish-brown spots on the surface. It stands out from other polished or red objects with a graphite coating due to its distinctive gloss and brightness.

Mauryan Architecture

Wood continued to be the material of choice even if there was a second shift to the usage of brick and stone at the time. Because of their durability, Kautilya advises the use of brick and stone in the Arthashastra. Nevertheless, he devotes a sizable section to measures to be taken to prevent fires in timber structures, highlighting their widespread use. According to the Greek ambassador Megasthenes, the Pataliputra capital city was surrounded by a substantial timber barrier with apertures or slits for archers to shoot through.

At Bulandi Bagh in Pataliputra, Spooner and Waddell excavated and found the remains of enormous timber palisades. Particularly interesting are the remains of an 80-pillared hall at Kumrahar, one of the buildings. Several stupas were built as brick and mortar mounds under Ashoka’s authority, including those at Sanchi, Sarnath, and most likely Amaravati. Unfortunately, they have undergone numerous renovations, so they no longer closely resemble the original buildings.

Coins

The Mauryans produced a range of shapes, sizes, and weights of mostly silver and a few copper coins with one or more symbols hammered into them. The most widely used symbols are the elephant, the tree on the fence sign, and the mountain. It was customary to cut the metal first, then punch the device while creating these coins.

UPSC CAPF Interview 2024 Dates Out: Chec...

UPSC CAPF Interview 2024 Dates Out: Chec...

UPSC Notification 2025: Download PDF, IA...

UPSC Notification 2025: Download PDF, IA...

CDS Syllabus 2025, Download Subject Wise...

CDS Syllabus 2025, Download Subject Wise...